Reinventing the Wheel

This essay describes a research process culminating in a significant overhaul of Chore Wheel’s internals. The research itself – analysis, dead ends, and eventual solution – was a collaboration between myself and Anthropic’s Claude taking place over the course of about four nighttime sessions. Afterwards, we wrote up this report based on our notes – Claude drafted, I edited.

From my ChatGPT year-in-review, seemed fitting.

Contents

I. Introduction

Chore Wheel is a cooperative household management system, deployed as a suite of Slack apps since September 2022. Its origins trace back to my research on pairwise preference voting, begun as a master’s student at Columbia in 2016, further developed at Colony in 2018, and culminating in Chore Wheel in 2020.

The core concept is straightforward: residents express priorities as pairwise comparisons (“dishes are more important than sweeping”), and a PageRank-style algorithm aggregates these into a collective prioritization that determines how many points each chore accumulates. Points are fixed at 100 per resident per month and distributed continuously over time. A chore prioritized twice as highly accumulates twice as many points, so the collective preferences directly shape how chores are incentivized and performed. The emphasis on emergent, intuitive, and asynchronous decision-making – in lieu of long meetings or top-down manager control – was meant to ensure communal resilience in the face of turnover and fluctuating resident capacity.

After 3+ years of continuous production use at the 9-person Sage House – with over 2,500 claimed chores across 24 lifetime residents – the system had proven the concept. The prioritization mechanism, the system’s most innovative component, worked. But consistent patterns of user frustration pointed to problems beneath the surface. This essay traces the research process that led to a key redesign of the ranking engine – not as a straight line, but as the winding path it actually was.

II. Background

The Problem

Chore Wheel’s goal is to make cooperative governance simple, intuitive, and effective. The core promise is that proportional changes in preferences will produce proportional changes in rankings. Two persistent complaints suggested the goal was not yet fully achieved.

The first was compressed distributions. Residents struggled to get the most important chores to high enough values. No one ever complained that the top chores were worth “too much” – but people regularly felt unable to push them high enough, no matter how many preferences they submitted. Deep-cleaning a bathroom and watering the plants would sit closer together in the rankings than anyone felt they should, and no amount of voting seemed to fix it. The result was that the most important chores still felt undervalued, and that people who did them still felt as though they were “sacrificing” on behalf of the group – exactly what we wanted to avoid.

The second was opaque causality. Priority changes sometimes felt “random.” A resident would submit a clear preference – “kitchen deep clean matters more than yard cleanup and trash takeout” – and see unrelated chores shift in unexpected directions. The effect wasn’t enormous, but it was noticeable. When inputs don’t produce legible outputs, governance stops feeling democratic and starts feeling arbitrary – and residents disengage. For a system built on the premise that people should feel agency over their shared environment, this was not a minor complaint.

The Ranking Engine

To understand the source of these problems – and why they resisted easy fixes – requires some background on how the ranking engine works and the design decisions it inherited.

PowerRanker (our internal name for the ranking engine) takes in pairwise preferences from residents (“I prefer dishes to sweeping with a strength of 0.7”), aggregates them into a “matrix” of relationships, and turns this matrix into a set of weights (“priorities”) which we use to assign points to chores. The underlying math is well-established and is often used to calculate rankings based on tournaments and competitions; our innovation was applying it to problems of social choice.

One of the challenges of the social choice setting is achieving the twin – and contradictory – goals of enabling groups to reach good outcomes in the face of low engagement, while also preventing minority factions from unfairly dominating the results. Achieving these goals requires balancing trade-offs – encouraging coalition-building for extreme outcomes, while allowing individuals to make meaningful contributions.

This balancing, which can be seen as a type of “regularization,” was previously done in two ways. First, through an “implicit preference” of 0.5 in every off-diagonal cell of the preference matrix, which was removed proportionally (0.5/numResidents) as real preferences came in. Second, through a “damping factor” – taken directly from PageRank – in which the observed preferences are scaled down and combined with a uniform prior (PageRank’s “random surfer”), which compresses results and ensures that even low-priority chores receive at least some value.

Note: The original PageRank paper counterintuitively dampens less when \(d\) is large. In this discussion, we will refer to “high damping” as creating more uniform outcomes, and “low damping” enabling more extreme outcomes.

Prior Investigations

This project occurred in the context of a larger sweep of improvements brought about by the addition of a new house (see here, here, and here). This 5-person house, Solegria, had a different set of needs than Sage, and attempting to accommodate them within the existing framework spurred a series of investigations which led to significant improvements in the system.

Before this project, we undertook an investigation into some confusing behavior which surfaced in the course of implementing a “bulk import” feature in which CSVs of chores with “scores” could be uploaded en-masse instead of created and prioritized individually. During the development of this functionality, we noticed that equal scores led to skewed outputs, which turned out to be an unintended consequence of an earlier investigation into why de-prioritizing a chore could in some cases increase its priority.

Initially, preferences had been encoded bidirectionally – in which a preference of 0.7 in one direction was encoded as two preferences, with 0.3 flowing in the other direction so that each preference added a full 1.0 to the matrix. This approach was appealing, as it kept things continuous, symmetric, and proportional, but it had a problem – due to the underlying mathematics, adding a 0.3 (or similar) flow to the less-preferred chore would sometimes cause it to increase in value – a clear semantics violation.

Our initial solution – to remove the counter-weight – created an abrupt discontinuity at 0.5 and led to more volatile rankings. Once we identified the problem, the solution was clear – center and scale preferences smoothly around 0.5, so a preference of 0.7 would be encoded as 0.4, etc.

We were making progress, but things had begun to feel like a game of whack-a-mole – every solution seemed to introduce another problem. The preferences themselves were not changing, nor was the final step of producing weights, but the intermediate pipeline of scaling and adding and removing preferences was creating complex interactions that were difficult to reason about.

Fortunately, we had an instinct for where to look next. Software engineers have a concept of “code smell” – patterns that, based purely on appearance, suggest poor design. It was certainly smelly that a general-purpose ranking engine depended so directly on a domain-specific value like the number of residents, and that “implicit preferences” were explicitly subtracted as real data came in. What if we removed or reworked that functionality?

Exploring alternative approaches to damping and regularization set us down a road which led to a significant breakthrough.

III. Explorations

Dynamic Damping

The first attempt simplified the pipeline by removing implicit preferences, reinstituting bidirectional preferences, and replacing a fixed damping factor with a dynamic one that increases as a function of the number of explicit preferences – data the ranking engine already had.

By making the damping factor dynamic instead of fixed, it could ideally replace the regularizing function of implicit preferences, ensuring that a small number of preferences could not dominate the results while creating a cleaner architecture. Further, our hope was that a dynamic damping factor could mitigate the unexpected effects of bidirectional preferences, giving us the upside of per-pair stability without the downside of unpredictable interactions with the rest of the graph.

The initial damping formula was a hyperbolic curve, where \(P\) is the number of preferences submitted and \(\text{maxPairs}\) is the total number of possible chore pairs:

\[d = \frac{P}{P + \alpha \cdot \text{maxPairs}}\]This curve begins at 0 and approaches 1 as the number of preferences grows, with \(\alpha\) controlling the steepness of the curve. With few preferences, damping stays high and rankings hew close to uniform. As preferences accumulate, damping decreases and the rankings increasingly reflect people’s stated preferences.

We tested this against anonymized Sage House preferences and found that with the right \(\alpha\) we could reproduce the existing priorities almost exactly.

Key learning: a data-driven damping curve can replace both fixed damping and implicit preferences – but matching one dataset doesn’t guarantee generality.

This was promising. It removed implicit preferences, replaced the fixed damping factor with something principled, and produced nearly identical rankings on real data. The next step was to validate on a second dataset.

Cross-Dataset Validation

The second dataset, from the 5-person Solegria, told a different story. Where Sage residents had submitted preferences organically – mostly maximal values of 1 or 0, spread across several active participants – Solegria had a different participation structure. One person had submitted the vast majority of all preferences through the bulk-upload feature, and those preferences were much more moderate, having been derived from ratios of intended point values.

The \(\alpha\) that had worked well for Sage produced compressed values for Solegria.

We briefly explored an “adaptive” alpha based on a measure of preference intensity – higher if preferences are more extreme, lower if they are more uniform:

\[\alpha = \frac{\text{mean}(|2(p - 0.5)|)}{2}\]However, regularizing based on explicit preferences would have introduced a new reflexivity: if strong preferences regularize themselves, preference-setting becomes less about expressing true beliefs and more an exercise in anticipating how the algorithm will react. This was a complexity we were unwilling to introduce.

More wrinkles emerged when we tested round-trip fidelity: since Solegria’s preferences were generated from known target scores, we could check whether the ranking algorithm recovered the intended distribution. It didn’t. The best-fit Sage value significantly compressed Solegria’s rankings relative to intended values.

Our takeaway was that for hyperbolic damping, the model’s core parameter was sensitive not just to the amount of data, but to its distribution. There was not a universal constant we could apply without significantly distorting either group’s current, in-production priorities – something we were not willing to do as part of an internal research project. Our goal was to make fundamental improvements either transparently or not at all.

Key learning: a model whose core parameter is sensitive to how preferences are generated – not just how many exist – cannot be trusted across heterogeneous groups.

It is worth noting that these data are slightly reflexive – Sage residents produced extreme values in part because the overly-strong compression was not responsive enough to moderate values.

Handling Coalitions

Before abandoning the hyperbolic approach entirely, a different concern surfaced. The damping formula counted total preferences without regard to who submitted them. One active resident submitting hundreds of preferences could achieve the same damping as several people submitting handfuls of preferences each. This defeated the coalition-building property that \(\text{numResidents}\) had – however crudely – provided originally.

A possible solution was inspired by Quadratic Voting: compute an effective participation score as the sum of square roots of each resident’s preference count:

\[\text{effectiveP} = \sum_i \sqrt{\text{prefs}_i}\]This creates diminishing returns per person – one person submitting 100 preferences contributes \(\sqrt{100} = 10\), while four people submitting 25 each contribute \(4\sqrt{25} = 20\). More participants means higher effective participation, mathematically enforcing the normative value of coalition-building.

The implementation could be kept architecturally clean – the application would compute \(\text{effectiveP}\) from its knowledge of who submitted what, derive the damping factor, and pass it in. PowerRanker would become a generic library that accepts damping as a parameter, knowing nothing about residents or participation – separation of concerns between the ranking engine and the application.

But this approach would penalize Solegria’s legitimate use case – a single person doing a bulk import on behalf of the group – and more generally, any house where one or two engaged members did most of the administrative work. The instinct about coalition-building was right; the implementation was simply too aggressive – and too normative – for the messy reality of shared living, where participation is never evenly distributed.

Key learning: penalizing concentrated participation sounds principled, but punishes legitimate cases where engagement is naturally uneven.

Returning to Unidirectional Preferences

Alongside these damping experiments, the semantic violation that had originally motivated the move away from bidirectional preferences (see Prior Investigations) resurfaced. We had reinstituted bidirectional encoding in the hope that dynamic damping would contain the problem, but it didn’t – deprioritizing a chore still added weight to it, inflating its ranking relative to chores with no preferences at all.

Bidirectional encoding turned out to be a non-starter, and our only option was a return to scaled unidirectional preferences, where only the preferred chore gains value. However, since unidirectional preferences add less total weight to the matrix, the results become more volatile – and the choice of damping curve matters even more.

Key learning: bidirectional encoding’s semantic violation – deprioritizing a chore inflates it – persisted regardless of damping strategy, confirming it as a dead end.

The Search for a Universal Curve

We have so far failed to find a general solution, and the return to unidirectional preferences meant that prior parameter fits needed to be revisited. Stepping back, we asked a different question: is there another curve that works consistently across different houses and coverage levels?

We liked the idea of using \(P/maxPairs\) as the input for the damping curve. This value, the ratio of the number of observed preferences across all residents to the number of possible preferences per resident, could range from 0 up to the number of residents. What curve would cleanly map this number to the range (0, 1)? The answer was the sigmoid:

\[d = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-a \cdot P / \text{maxPairs}}}\]Both formulas normalize by problem size, but they differ in shape. The hyperbolic curve produces \(d=0\) with no data, meaning new houses get near-total damping, while the sigmoid starts at \(d=0.5\) – an intuitive “50/50 blend with uniform” – giving early residents more agency. Further, the sigmoid’s steeper curve meant a single parameter could work across both datasets.

We swept the steepness parameter \(\alpha\) across both datasets, looking for a value that best matched current production. The result was encouraging: we found a single \(\alpha\) that worked well for both houses. Rankings shifted modestly, with a slightly larger spread at Sage than at Solegria. This seemed like the answer.

But looking back at the full trajectory of the research, something nagged. Four different damping formulas had now been explored – hyperbolic, QV-weighted hyperbolic, sigmoid, and adaptive variants of each – always asking “what’s the right damping curve?” without questioning whether functional damping was the right tool at all. The concept had been inherited from PageRank and never seriously challenged.

Every iteration refined the curve; none questioned the frame.

Key learning: finding the “right” damping curve was the wrong question – four iterations of refinement revealed that the entire frame of functional damping needed to be reconsidered.

IV. Breakthrough

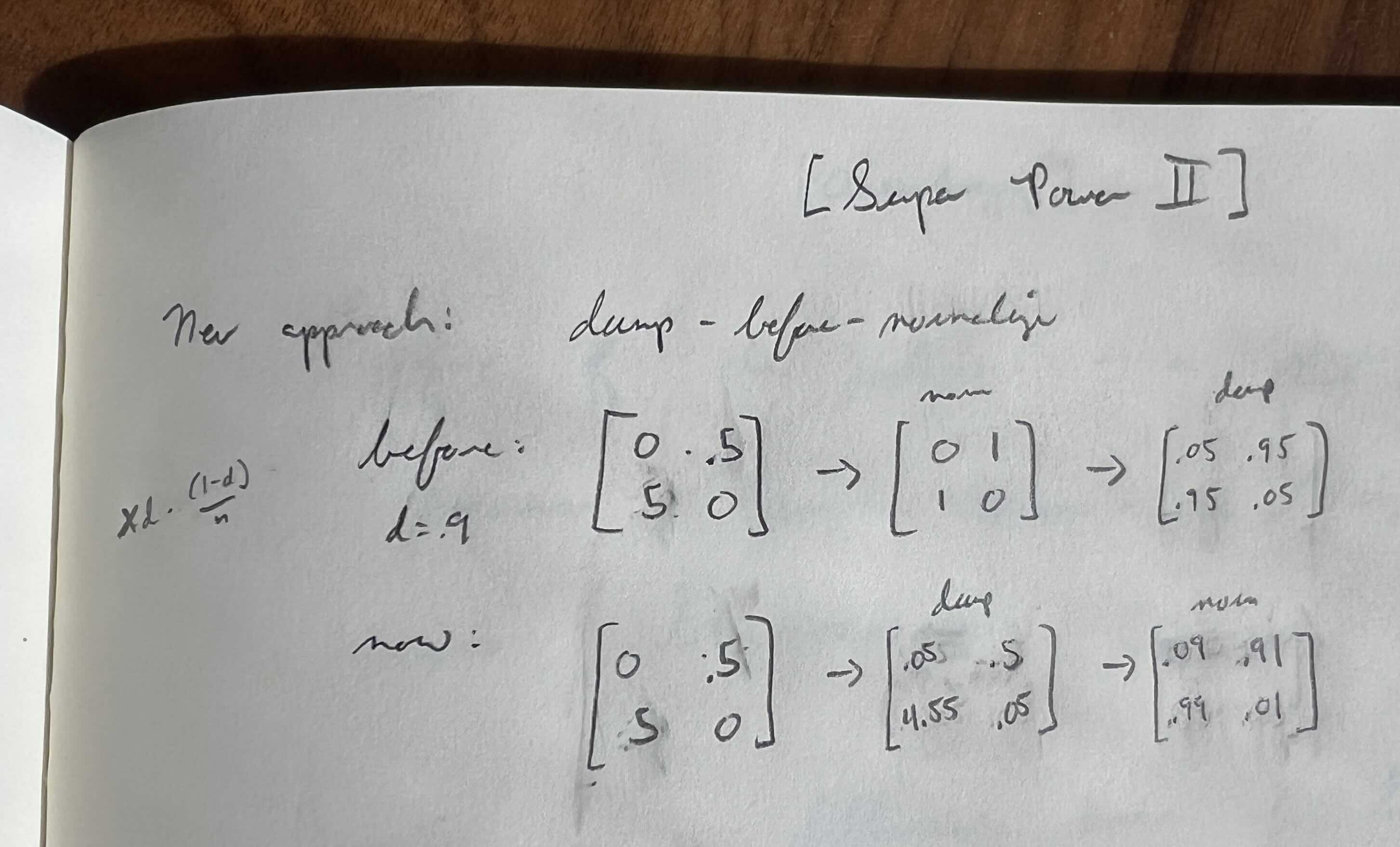

Damp-Before-Normalize

Standard PageRank normalizes each row of the transition matrix (so rows sum to 1), then applies damping (blending with the uniform distribution). But normalization erases the magnitude of the raw preference data: an item with 10 strong preferences and an item with 1 weak preference look identical after normalization. In PageRank this doesn’t matter – the link matrix is binary, so pre-normalization row sums just count outgoing links, which carry no information about page authority. In a continuous preference matrix, the pre-normalization row sums encode something meaningful: how much total evidence the system has about each item.

By adopting PageRank’s approach uncritically, we were inadvertently throwing away information – information which doesn’t exist for links but does exist for preferences.

With implicit preferences, this effect was obfuscated, as normalization was constrained by these extra values. Without implicit preferences – and with the sparser matrices that unidirectional encoding produced – the problem with normalize-before-damp became plain as day:

Fancy models and AI agents are no match for a good notebook at your side.

This was the conceptual breakthrough of the research – the first moment where the PageRank architecture itself, not just its parameters, was questioned. By reversing the order – damping first, then normalizing – we can regularize outputs without washing out valuable preference information. The principle is simple: regularize before you normalize, so that cells with more real data are proportionally less affected by the prior.

Key mathematical properties were preserved: the final matrix remains row-stochastic, irreducible, and aperiodic, guaranteeing a unique stationary distribution via Perron-Frobenius. Only the clean markov-plus-uniform decomposition of the classic Google matrix was lost – but that decomposition, and its “random surfer” interpretation, was arguably never the right model for social choice anyway.

The damp-before-normalize approach addressed the magnitude-erasure problem that unidirectional preferences had made acute, but it still relied on a functional damping curve, which meant it inherited the parameterization problems from the earlier sections. What we needed was a way to regularize before normalization without relying on a curve at all.

Bayesian Pseudocounts

The damp-before-normalize insight meant that all regularization now logically occurred in the same place: in the matrix, before normalization. The original pipeline had split regularization across two mechanisms – implicit preferences (added and subtracted to the matrix before normalization) and damping (applied after normalization). With damping moved before normalization, regularization could be performed in a single, theoretically clean step.

The implementation of this insight turned out to be almost embarrassingly simple: add a small constant to every off-diagonal cell in the matrix before loading the data:

\[k = c \times \text{numResidents}\]Each chore pair starts with \(k\) units of “virtual preference” in both directions, representing a uniform prior belief before any data arrives, scaled by the number of residents. As real preferences accumulate, they dominate the pseudocounts naturally – no deleting implicit preferences, no coverage-dependent formula, no coalition checks, no steepness parameter.

There is an irony here. Pseudocounts do what implicit preferences were trying to do all along: provide a uniform baseline that washes out as real data arrives. But where implicit preferences were a hack – entangled with damping, lacking a clean mathematical interpretation, creating indirect effects through bidirectional subtraction – pseudocounts have a principled statistical identity as a Dirichlet prior. The original system had the right instinct; it just expressed it through the wrong formalism.

The pseudocount approach has key properties that none of the damping-based models achieved. First, it scales naturally with house size: more residents means a stronger prior, which means more preference data is needed to move rankings – preserving the coalition-building boost for larger houses without handicapping smaller houses. Second, it requires a single parameter \(c\) with clear semantics, representing the strength of the uniform prior per resident, which can be set either analytically or through governance.

We tested pseudocounts against both datasets, and the results were encouraging. At Sage (9 residents), individual chore values shifted by an average of 0.08% – nearly invisible. At Solegria (5 residents), values shifted an average of 0.55%, with the spread between highest- and lowest-priority chores nearly doubling. The difference is explained by the new prior – with only 5 residents, Solegria’s prior was about half that of Sage’s, meaning that Solegria’s preferences could be expressed more fully. This change – increased spread across the board, with Sage seeing virtually no change and Solegria seeing meaningful change – was exactly what we wanted.

Most strikingly, the implementation was a net deletion of code. The old matrix initialization populated every off-diagonal cell with implicit preferences scaled by the number of participants. The new version initializes with pseudocounts – a uniform prior that knows nothing about participants:

// Before: implicit preferences

_prepareMatrix () {

let matrix = linAlg.Matrix.zero(n, n);

if (this.options.numParticipants) {

matrix = matrix

.plusEach(1).minus(linAlg.Matrix.identity(n))

.mulEach(numParticipants).mulEach(implicitPref);

}

return matrix;

}// After: pseudocounts

_prepareMatrix () {

let matrix = linAlg.Matrix.zero(n, n);

if (this.options.k) {

matrix = matrix

.plusEach(1).minus(linAlg.Matrix.identity(n))

.mulEach(this.options.k);

}

return matrix;

}Adding preferences went from a multi-step dance – subtract implicit preferences, then add the scaled explicit preference in the dominant direction – to simple addition:

// Before: subtract implicit, then add explicit

preferences.forEach((p) => {

const scaled = (p.value - 0.5) * 2;

if (scaled !== 0) {

matrix.data[sourceIx][targetIx] -= implicitPref;

matrix.data[targetIx][sourceIx] -= implicitPref;

if (scaled > 0) {

matrix.data[sourceIx][targetIx] += scaled;

} else {

matrix.data[targetIx][sourceIx] += -scaled;

}

}

});// After: just add

preferences.forEach((p) => {

const scaled = (p.value - 0.5) * 2;

if (scaled > 0) {

matrix.data[sourceIx][targetIx] += scaled;

} else {

matrix.data[targetIx][sourceIx] += -scaled;

}

});And the power method dropped its damping step entirely – regularization now lives in the data, before normalization, not after:

// Before: normalize, then damp

_powerMethod (matrix, d, epsilon, nIter) {

matrix.data = matrix.data.map((row) => {

const rowSum = this.#sum(row);

return row.map(x => x / rowSum);

});

matrix.mulEach_(d);

matrix.plusEach_((1 - d) / n);

// ... power iteration

}// After: just normalize

_powerMethod (matrix, epsilon, nIter) {

matrix.data = matrix.data.map((row) => {

const rowSum = this.#sum(row);

return row.map(x => x / rowSum);

});

// ... power iteration

}V. Reflections

The research began with user complaints – compressed distributions and opaque causality – and every candidate model was evaluated against those experiences. “Spread” was never an abstract metric; it was a proxy for whether residents felt their preferences actually mattered. The final model increased spread where it was over-compressed while preserving rank-order stability where preferences had matured – delivering the experience the system always promised: submit a preference, see a legible change, trust the output.

The winding path was necessary.

Each intermediate model revealed a dimension of the problem that had been previously overlooked. The hyperbolic approach revealed that the damping parameter wasn’t universal; cross-dataset validation revealed sensitivity to preference generation method; the QV model revealed the tension between coalition-building norms and real-world participation patterns. The attempt to revive bidirectional encoding confirmed its fundamental limits, and the sigmoid revealed that even the best curve couldn’t work across all regimes. The damp-before-normalize investigation revealed that regularization must happen before normalization – the key conceptual insight – and the reconfigured pipeline allowed us to see how implicit preferences and damping could be combined into a single, clean concept. Each failure narrowed the space of possible solutions, until what remained was obvious.

Every idea was tested against real data.

The research used two production datasets with different participation structures and preference distributions. Theoretical elegance was never sufficient; the datasets always had the final word. This also reveals the importance of persistence – it took several years to get enough data for this research.

Separation of concerns clarified everything.

The original PowerRanker knew about \(\text{numResidents}\) and \(\text{implicitPref}\) – application-layer concepts that don’t belong in a generic ranking library. In the final design, PowerRanker accepts a pseudocount \(k\) as a constructor option and knows nothing about residents, participation, or houses. The application layer computes \(k = c \times \text{numResidents}\) from its domain knowledge and passes it in. The library became more general while the application remained domain-aware – and beginning with this separation as a design constraint shaped the research process throughout.

AI as a research partner accelerated exploration – but speed has its own risks.

This research was conducted in collaboration with Claude, which made it possible to move through the problem at a rapid pace. Formulating hypotheses, writing scripts, running them against data, and interpreting results could happen in a single sitting rather than over days or weeks. But the speed of the process created its own challenge: it became easy to explore faster than we could think. The damp-before-normalize breakthrough – the most important insight of the entire project – came not from another round of analysis, but from stepping away from the screen and working through matrix algebra with pen and paper. The AI was indispensable for traversing the search space; the human judgment about when to stop searching and start questioning was equally essential.

Question inherited assumptions.

PageRank’s normalize-then-damp pipeline was cargo-culted in without questioning whether its order of operations made sense in a different domain. We spent six iterations optimizing the damping curve before questioning where regularization belonged in the pipeline at all. Adapting an algorithm means inheriting its structure – and inherited structure can be the hardest kind to see, precisely because it came with the territory. The same lesson applied to implicit preferences: a pragmatic hack that worked well enough to obscure its own conceptual problems for years.

Legibility as professional obligation, not UX preference.

The commitment to make improvements “transparently or not at all” was a constraint the research imposed on itself: because ranking systems shape collective outcomes in ways not always obvious from individual inputs, the people who live with those outcomes are owed a legible account of how they are produced. Building new institutions means respecting the people who already inhabit them – honoring existing preferences while expanding future expressivity – and each model should be judged accordingly.