The Pairwise Paradigm

Abstract: Pairwise methods are best thought of as composing a paradigm for turning scarce attention into robust allocation signals. With the right algorithms, interface, and audience, they can support the continuous funding of ecosystems at surprisingly low attention cost.

Thanks to Carl Cervone, David Gasquez, and Ori Shimony for feedback on earlier versions of this essay.

- I. Motivations

- II. Why Pairwise

- III. The Pairwise Paradigm

- IV. Continuous Funding

- V. Evaluation and Legitimacy

- VI. Additional Considerations

- VII. Putting It All Together

I. Motivations

There is no perfect voting system. The truth and tragedy of this statement have been understood for decades, beginning with Kenneth Arrow’s “impossibility theorem” showing the fundamental limits of ranked-choice voting systems.

At its core, the problem stems from attempting to measure complex social reality under conditions of high stakes. In attempting to distill subjective reality into objective votes, information is lost, and the measurement process itself becomes an arena for power contestation. In the end, the best we can do is design task-specific systems in which the gap between subjective experience and objective input is as small as possible, decreasing the scope of conflict and increasing both the utility and legitimacy of these systems.

In mid-2019 I speculated that, within the web3 governance community, the limitations of pass-fail voting would shift interest away from proposal-based decision-making towards distributed capital allocation. Over the last six years, that prediction has largely been borne out: instead of voting on policy, governance innovation has increasingly come to revolve around giving out money. The shift from discrete policy outcomes (you win, I lose) to continuous financial outcomes ($10 to you, $5 to me) opens a rich design space for social choice.

Within this domain, several classes of techniques have been explored:

- Quadratic Funding, in which direct donations double as “votes” dividing a matching pool, subject to square-root constraints.

- Pairwise Methods, in which inputs are framed as “A vs B” and converted into numeric allocations via an algorithm.

- Metrics-Based, in which votes are made on high-level metrics, and allocations are made indirectly based on these metrics.

- AI-Augmented, in which AI agents analyze projects and recommend allocations based on various internal processes.

Each of these approaches, on some level, seeks to convert scarce attention into useful signal. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses:

- Quadratic Funding advantages smaller groups, but struggles to allocate attention, leading to “beauty contests.”

- Pairwise Methods offer a simple and intuitive framing, but struggle to get sufficient coverage to produce good results.

- Metrics-Based reduce scope for politics, but struggle with “Goodhart’s Law” failures and incentivize misrepresentation.

- AI-Augmented sidestep issues of voter apathy, but struggle with issues of alignment, legitimacy, and interpretability.

I have been researching and working with decision-making systems since 2016, with a focus on pairwise methods. I believe that we should continue exploring all of these techniques, and develop a culture of practice able to select from among them based on the characteristics of the problem, and audience, at hand.

The rest of this essay will discuss pairwise preferences specifically, and describe the design space in which they operate. We will argue that pairwise methods should not be understood as isolated mechanisms, but as part of a larger paradigm of decision-making incorporating multiple complementary techniques. By approaching pairwise methods as a paradigm, it becomes easier to see how the various elements combine into a high-performance system for allocating shared resources.

We will focus on the use-case of “public goods funding,” in which communities come together to fund critical infrastructure, as this is the domain with the most activity and richest basis for analysis. The scope of these methods, however, is broader: instead of funding public goods, we could apply these methods to problems as grand as the setting of federal budgets, or as mundane as judging hackathons or prioritizing chores in a coliving house. Given the range of possible applications, getting pairwise right would be a major unlock in our ability to coordinate at scale.

II. Why Pairwise

A pairwise preference is a relative choice between two options, A or B. Pairwise preferences are the atoms of human subjectivity: the simplest distinction a person can make, running on the “phenomenological bare metal” of perception. This simplicity makes them robust (they mean what they say they mean), accessible (anybody can make a relative distinction), general (many decisions can be framed in relative terms), and flexible (pairwise preferences can be aggregated in many different ways).

Note: contrary to some depictions, Tinder-style swipes are not pairwise judgments, but pass/fail decisions.

Pairwise preferences have been studied for decades, going back to the work of American psychometrician L. L. Thurstone in 1927 and his research into subjective responses to stimuli. Pairwise preferences would find many applications in the ranking and ordering of items: from ranking chess players with Elo, to weighting web pages with Google’s PageRank, to assessing the reliability of nodes in a peer-to-peer file-sharing network with EigenTrust, to allocating credit for open-source contributions with SourceCred.

This dual heritage, as a technique for subjective measurement and allocating weights among items, suggests these methods have much to offer to the practice of distributed capital allocation, which faces exactly these problems.

USV’s Albert Wenger recently argued that “capital allocation is often downstream from attention allocation.” As society increasingly comes to view attention as its scarcest resource, evaluating social choice schemes through the lens of attention becomes increasingly critical. When compared to other voting systems, pairwise methods are arguably more “attention-native” – stimulating, game-like, and inherently rewarding to engage with.

Unlike non-attention-native methods like quadratic funding, which often lead to “beauty contests” favoring projects with marketing muscle, pairwise methods more naturally distribute attention by presenting items in random pairs. This approach elevates item discovery into a first-class construct, as voters are frequently exposed to items with which they are unfamiliar. This reduces the need (and benefit) for projects to market themselves, freeing resources for driving engagement with the system as a whole.

Further, distributing voter attention makes strategic voting more costly. Unlike, for instance, a Borda Count, in which one can trivially “bury” a rival by listing them last, voter evaluations will involve many pairs of items in which they have no strategic interest.

Seen through this lens, pairwise methods appear as a natural basis for social choice in an environment of scarce attention. Rather than take voting methods designed for pen and paper and try to adapt them to fast-paced, digital decision environments, we can take decision primitives designed for attention and make them the core of an entirely new regime.

Despite these attractive qualities, pairwise methods remain niche. They have seen some use in public goods funding, such as in Optimism’s RetroPGF (helping to allocate $100mm+ in funding) as well as in this year’s Deep Funding initiative, but have yet to capture the enthusiasm of other techniques.

This is in part due to gaps in pairwise practice, as well as the lack of an overarching vision – making the technique difficult to use and to communicate. By clearly articulating pairwise as a paradigm of interrelated techniques, we can better communicate the scope of these methods, build momentum around their use, and advance the art and practice of public goods funding overall.

III. The Pairwise Paradigm

The word “paradigm” comes from the Greek word for “pattern,” and in scientific contexts refers to “a distinct set of concepts or thought patterns, including theories, research methods, postulates, and standards for what constitutes legitimate contributions to a field.” By framing pairwise as a “paradigm” instead of a single tool or mechanism, we emphasize that it is not any one technique, but rather the synergies between techniques that produce desirable outcomes.

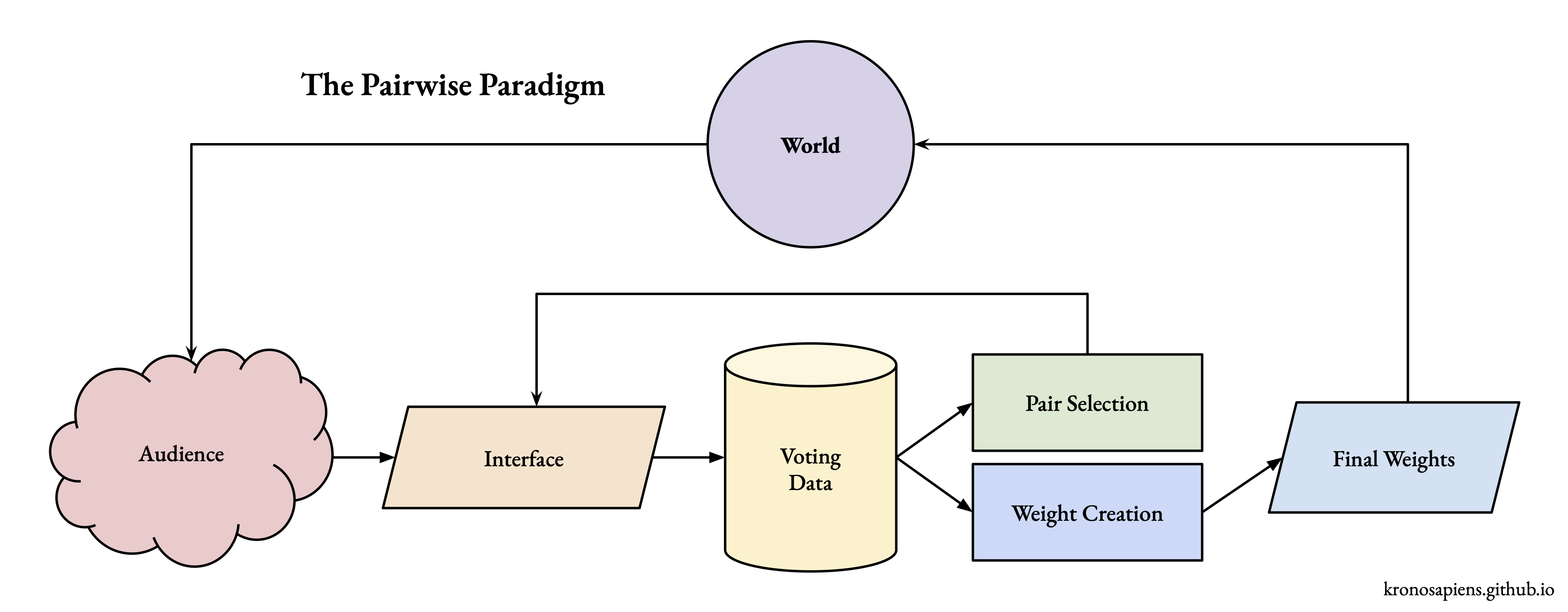

These techniques fall into multiple buckets: audience and problem development, interface design and data collection, and algorithmic data analysis. As an end-to-end pipeline, audiences feed into a voting interface, which feeds data to algorithms that guide both ongoing data collection and final analysis:

Individual techniques can be added, altered, or removed within this pairwise paradigm, allowing for parallel explorations within a coherent design space.

We will now explore these topics, starting with algorithms (what we’re trying to compute), then work backward through pair selection, interfaces, and audience – the layers that shape the data those algorithms receive.

1. Algorithm Selection

Note: this section is more technically dense than the rest of the essay. Feel free to skim if the details are not relevant to you.

Pairwise preferences themselves do not determine rankings or weights. Rather, they must be converted into weights using an algorithmic process, a “machine for converting subjectivity into objectivity.” The choice of algorithm has far-reaching implications for what kind of output gets created, and how it should be interpreted.

This section will discuss several options and their properties, with a focus on the ontology and complexity of each algorithm – how each algorithm models reality, and how it processes information relative to that model.

In all cases, we begin with a sequence of pairwise observations \([(a, b, x), ...]\) with \(x\) representing the pairwise judgment, and want to produce a set of weights \(w = [w_a, w_b, ...]\) telling us how to divide a fixed pool of capital among the items.

Note: Throughout this section, we will use the standard “Big-O” notation for evaluating the complexity, in terms of both computation and data, of these techniques.

Elo

The Elo rating system, developed by Hungarian chess master Arpad Elo, is most well-known as the basis for professional chess rankings, but has found use in determining rankings across a variety of domains.

In the Elo system, every participant has a rating \(R\) determined by their prior matchups, used to predict the score of an upcoming match between \(a\) and \(b\):

\[E[S_{ab}] = \frac{f(R_a)}{f(R_a) + f(R_b)}\]After a match, the players’ Elo ratings are updated as a function of the actual outcome vs the predicted outcome against an opponent:

\[R'_a \leftarrow R_a + g(S_{ab} - E[S_{ab}])\]Ontologically, Elo models interactions as occurring in a sequence between the entities themselves, with the entities changing as a result of these encounters.

Computationally, Elo is \(O(n)\) in the number of matchups \(n\), with every matchup resulting in one constant-time update, with no minimum number of observations.

Unlike the other algorithms discussed, which generate weights in a single batch using all of the observed preference data, Elo is an online algorithm, meaning that the rankings are updated after every matchup – and are thus dependent on the specific sequence of the matches. Data are understood as the result of a matchup between two items, not as a vote on a pair of items by an independent observer.

While often proposed as a candidate algorithm for capital allocation, Elo’s ontology of a sequence of matchups between items makes it a bad fit for the use-case, in which data takes the form of a set of votes by third-party observers.

Bradley-Terry

The Bradley-Terry model is a popular model for generating weights based on pairwise preferences.

Bradley-Terry models every item as having a latent strength \(p\), and models the probability of item \(a\) being preferred to item \(b\) as follows:

\[P(a > b) = \frac{p_a}{p_a + p_b}\]Ontologically, Bradley-Terry is essentially Platonic: pairwise observations are understood as random fluctuations revealing a hidden capital-T Truth.

Computationally, fitting a Bradley-Terry model is \(O(nm)\) in the number of matchups \(n\) and number of iterations \(m\) needed to converge, requiring observations \(O(k^2)\) in the number of items \(k\).

Note the similarity to Elo, which also models results as a ratio of latent scores. However, unlike Elo, Bradley-Terry produces weights in a batch based on a set of unordered preferences, making it a more natural choice in the setting where the inputs have no inherent ordering. In terms of computational complexity, Bradley-Terry models are typically fit using a statistical technique of Maximum-Likelihood Estimation, in which the underlying probabilities are iteratively updated to improve their fit to the observed data, requiring several passes, or iterations, over the training data.

Bradley-Terry methods are popular in the academic literature, as they lend themselves well to evaluation and simulation – one can begin with a fictional “ground truth,” run a simulated voting process, and then evaluate how well the recovered weights align with the initial ground truth. These types of simulations, while rigorous in the statistical sense, tell us less than we might like about how these models perform under real-world conditions.

Spectral Methods

Spectral methods, the most famous of which is Google’s PageRank, aggregate pairwise inputs into a “graph” of interactions, and then take the weights from the graph’s principal eigenvector.

In linear algebra, the eigenvector (“self-vector”) of a graph or matrix \(X\) is the vector \(v\) such that:

\[Xv = \lambda v\]We can interpret this vector as representing the “direction” to which the graph “points,” which we can interpret as a type of “center” or “steady state” of the data (see visualization). Techniques for decomposing a graph into these components are known as “spectral methods” after the “spectrum” of latent values they reveal (just as white light is divided into a “spectrum” of constituent colors).

Ontologically, spectral methods invert the Bradley-Terry model by taking interactions as the only knowable reality; weights are understood as summary statistics, not hidden truths.

Computationally, spectral methods are \(O(k^3 + n)\) in the number of items \(k\) and the number of matchups \(n\), requiring \(O(k^2)\) observations. That the computation grows with the number of items, not the number of votes, makes this technique shine in settings where many votes are cast on a small number of items.

Note: spectral methods naively require \(O(k^2)\) observations, but smart pair selection can reduce this to \(O(k)\) (see “active ranking” below).

Spectral methods have a history dating back to German mathematician Edmund Landau, who in 1915 described how they could be used to judge the outcomes of competitions. In this setting, “votes” emerge endogenously from interactions among the items themselves (i.e. two teams competing with each other, two websites linking to each other). In 2018, inspired by projects like Pol.is and All Our Ideas, my colleagues at Colony and I extended these techniques to the domain of social choice, modeling votes emerging exogenously as voter judgments. This work led to the development of pairwise.vote, the preferred pairwise interface for web3 public goods funding, used in both Optimism’s RetroPGF and the first iteration of this year’s Deep Funding initiative.

Among researchers, spectral methods were historically neglected relative to Bradley-Terry until the 2015 Rank Centrality paper demonstrated both their statistical equivalence and computational advantages. The key theoretical difference between the models is that spectral methods evaluate relationships globally and leverage transitive relationships not explicitly observed: if A beats B, and B beats C, then a spectral method can infer that A likely beats C. This propagation of signal creates more complex interactions, but also allows these methods to produce better results with the same information. Spectral methods are also robust against cycles and other intransitive relationships, for which they produce ties, not contradictions (see “intransitivity of preferences” below)

For these reasons, we believe spectral methods are a strong choice for capital allocation, which cares about modeling relationships across an entire ecosystem.

Deep Funding

Both Bradley-Terry and spectral methods have a major drawback: they are data-hungry, requiring votes on the order of \(O(k^2)\), the square of the number of items \(k\). These large data requirements make pairwise methods difficult to use in practice, as they make gathering sufficient data challenging.

Deep Funding is an alternative technique proposed by Vitalik Buterin in late 2024, in which pairwise judgments are not used to generate weights directly, but rather to score competing weight proposals, which are produced externally.

Note: this initiative is unrelated to SingularityNET’s Deep Funding program.

Under the slogan of “AI as the engine, humans as the steering wheel,” Buterin introduces a model of social choice in which the weight proposals are produced at scale by machines, with a relatively small amount of human input being used to score proposals. This reframing of the problem – and of the role of voters – aims to produce better results with less human input, and can be seen as an alternative response to the attention problem we introduced earlier.

Ontologically, Deep Funding treats weights as untrusted proposals and treats juror inputs as samples of reality used to score and select the best proposals.

Computationally, Deep Funding is \(O(nw)\) in the number of votes \(n\) and the number of proposals \(w\), requiring data on the order of \(O(k)\) in the number of items.

Given that weights are not derived from votes directly, Deep Funding may be better understood as a meta-algorithm than as a pairwise algorithm proper.

Unlike the \(O(k^2)\) vote requirement of Bradley-Terry and the spectral methods, Deep Funding aims to produce results with only \(O(k)\) votes and a small constant factor, on the order of \(k/10\), or one vote for every ten items. This reduction in complexity from quadratic to linear means that Deep Funding methods can be applied to problems with many items, for which it would not be feasible to gather a large number of pairwise judgments.

Note that this smaller data requirement does not take into account the computation needed to create the weight proposals themselves.

Deep Funding’s central drawback is that the \(O(k)\) votes are only enough to score proposals, not to produce them. Ultimately, the method can only produce results as good as the proposals it receives, introducing new vectors of complexity, risk, and disruption.

2. Pair Selection

As mentioned earlier, a challenge of using Bradley-Terry and spectral methods is that they require a quadratic number of votes for a given number of items. As a result of this explosion of interactions, producing weights for even 50 items might call for 2,000 votes – a big ask, especially for communities already struggling with voter apathy.

Developing techniques for managing this scale will be key to bringing pairwise methods into the mainstream.

Fortunately, two practical approaches already exist: star grouping and active ranking.

Star Grouping

This approach, developed by the team at General Magic, introduces a pre-filtering step in which voters score each project on a scale of one to five stars. These scores then bucket projects into one of five tiers, with pairwise comparisons being made only between projects of the same tier. This reduces the number of votes required by 80%, by ensuring that the quadratic creation of pairs occurs in smaller sets.

Star grouping can also be adapted to settings where the categorization is not of quality, but of type. In cases where the items being considered are not all of the same type, star grouping can cluster like items together, clarifying downstream voting.

Active Ranking

Another approach for reducing the number of votes needed is through a technique called “active ranking,” an adaptation of the “dueling bandits” algorithm from machine learning.

Active ranking works by surfacing pairs not at random, but based on the uncertainty of that pair. The intuition is that among the entire set of items, some pairwise judgments are more “obvious” than others, and so don’t need to be voted on (e.g. bear vs rabbit). Active ranking directs scarce voter attention to the pairs which are the most ambiguous, and thus provide the most information (e.g. bear vs lion).

In theory, we can imagine needing as few as \(O(k)\) votes, albeit with a large constant factor – an entirely different complexity class from \(O(k^2)\).

To give intuition for why this should be possible, observe that any weighting of \(k\) items can be expressed as a set of \(k-1\) scalars (up to an overall scaling factor), representing the pairwise ratio of two adjacent items:

\[[.1, .2, .3, .4] \rightarrow [2, 3/2, 4/3]\]This generalizes to an arbitrary number of weights and suggests to us that we can in principle construct \(k\) weights with only \(k-1\) human inputs. While this limit is not achievable in practice, we can attempt to approach it, reducing the data requirement to some multiple of the number of items, i.e. \(k \cdot 10\) by directing attention towards the subset pairs which are most competitive with each other.

Note: the estimate of 10 votes per item is speculative and depends on the specific structure of the graph; real-world performance will need to be evaluated in future research.

Implementing active ranking is surprisingly straightforward. For every pair of items \(a, b\) we construct a Beta distribution \(p_{ab} \sim Beta(votes[a,b], votes[b,a])\) representing the ambiguity of the pair, and then sample based on \(Var(p_{ab})\). This variance will be high for pairs with few or mixed observations, and low for pairs in which one item is repeatedly preferred – directing voter attention to where it is most valuable. Calculating these distributions can be done iteratively, with the relevant distribution being updated in constant-time after each vote.

Compared to star grouping, active ranking has several advantages. First, active ranking permits \(O(k)\) comparisons total, while star grouping implies \(O(k^2)\) votes per tier. Second, active ranking can be run transparently in the background, while star grouping requires an explicit voting step. Third, active ranking allows for all projects to be compared, whereas star grouping precludes comparison between groups.

Note that active ranking is an online process – the order of votes does matter for determining which pairs are more likely to be shown, although the final weight production remains a batch process using all available data. This online nature of active ranking creates a new attack vector, as prior votes now influence the likelihood of future items being shown. Mitigating this risk will be an important part of bringing active ranking into production.

3. Interface Design

Another key consideration is the design of the voting interface. A data analysis pipeline is only as good as the quality of the data it analyzes. More so than with other methods, the interface of a pairwise process has significant impact on the quality of the data collected.

To illustrate this, imagine a hypothetical “bad” interface, showing only the names of the items being compared. With this interface, participants must make decisions based only on their pre-existing associations, resulting in noisy and unreliable data. In an even more extreme example, imagine a user deciding between two random strings – a process which produces pure noise.

Taking it in the other direction, can you imagine an interface profoundly better than any you’ve seen before? Why or why not?

Ultimately, the performance of a pairwise voting system is downstream of the interface.

Voting and Session Times

Before getting into the specifics of UI elements, we should ask ourselves a basic “product” question: how long should voters spend evaluating a given pair? With a target time in mind, we can work backwards to make decisions about visual design.

In discussion, practitioners have proposed target decision times of as short as 5 seconds to as long as 5 minutes. Analysis of deep funding voting data suggests that the “sweet spot” is about 30 seconds. More time does not result in meaningfully better judgments, and reduces the total number of pairs submitted. Less time increases the likelihood of a random choice, and thus of measurement error.

Working backwards from this 30-second target, we can design an interface to provide as much information as can be processed in that time frame.

Beyond individual votes, we can also think about the voting “session” as another type of product. If we see voting on a single pair as the atom of a pairwise process, a 30-second decision bundles naturally into the 5-minute voting sessions, yielding 10 new votes. The 5-minute session becomes the unit of engagement – light enough to be completed on the train or over coffee, yet substantial enough to move the process forward.

Input Format

Another key question is whether voters will be asked to make ordinal judgments (A better than B) or cardinal judgments (A 3x better than B). While cardinal judgments are appealing at first glance, offering the promise of more signal, that promise is often unfulfilled. It is typically the case that in untrained audiences, measurements of psychic intensity are more likely than not to be measurements of individual mood or personality, yielding mostly noise and little signal.

An analysis of Deep Funding’s initial juror data showed that while the perceived numeric ratio of two projects’ impact varied widely, the perceived direction of the impact (whether A or B overall was more important) was remarkably consistent – between 63% and 89% agreement, depending on the set of items being evaluated. This implies that while voters struggled to provide consistent numeric evaluations of the relative impact between pairs of projects, they could more consistently determine which of two projects was more impactful overall.

It is, of course, not so simple, and questions of cardinality and ordinality continue to be explored by the academic community. One recent paper on LLM evaluation found that models which presented results with “distractions” like excess enthusiasm were more likely to be chosen in ordinal matchups, while both neutral and “distracting” responses received similar cardinal ratings, suggesting that, at least in the case of LLM judgment, cardinal methods may be robust in ways that ordinal methods are not. Another recent study found that over long periods of time, cardinal measures of personal wellbeing were correlated with objective outcomes (such as moving to a new neighborhood if unhappy where you live), suggesting that cardinal judgments are not always noisy or idiosyncratic, but consistently capture sentiment at scale.

The question of cardinal vs ordinal judgments is far from settled, and much depends on the specifics of the problem and the audience. However, it does seem that in our setting of decentralized capital allocation by large heterogeneous groups of voters, that ordinal judgments should be, at the very least, the default.

Visual Elements

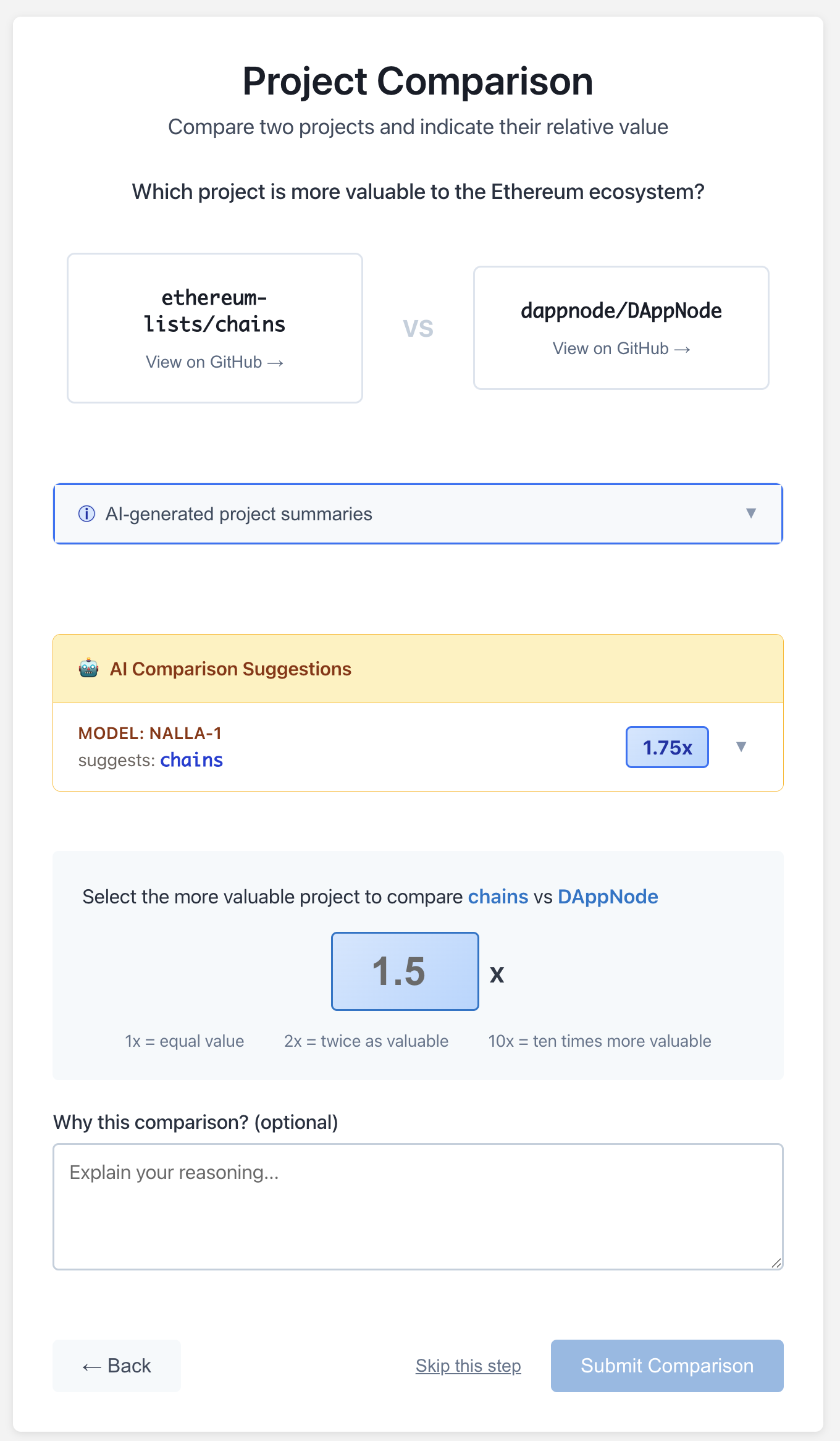

When it comes to visual design, the Pairwise team has arguably gone the furthest. Consider the interface they developed for the Deep Funding pilot:

Here we see a number of design elements:

- Each item clearly indicated by name and logo

- A set of curated and domain-specific metrics

- An AI-based textual summary of the project

- The ability to choose either item, or to skip

These elements form the foundation of an effective decision process. The metrics enable immediate, quantitative contrast between the two items, while the text summary gives the voter deeper context on individual items. Letting the voter skip pairs reduces the incidence of bad data, in cases where a voter genuinely cannot differentiate between two items.

Further, this approach leverages both metrics and AI judgment, while leaving the final decision in the hands of human voters. The key insight is that while the metrics and summaries may be the same for every project, individual voters qualitatively integrate the information differently, yielding richer results than would be possible by allocating funds by metric or AI judgment directly. Pairwise methods are more robust to Goodhart’s Law-style failures, common among metric and AI-based approaches, in which projects learn to “game the system” by tailoring their self-representation to more narrow and mechanical decision criteria.

Here is another interface example, Verdict, recently developed by the Deep Funding team:

This interface is organized around the idea of “high quality bits” and reflects the team’s priors around data quality and their desire for fewer, highly selected votes. This interface asks voters to make cardinal assessments of relative value, and asks for written explanations for their decisions. In addition, the interface states that all votes will be reviewed by “meta-jurors” and potentially rejected if deemed unjustified.

This interface was developed following the initial pilot, which used the Pairwise.vote interface presented previously. When analyzing the data from that pilot, the Deep Funding team found that their cardinal rankings varied significantly in scale and range per-voter. Rather than adopt ordinal inputs, which are more robust to voter idiosyncrasies, they chose to increase gatekeeping as a way of maintaining data quality. It retains the use of AI summaries, but omits the metrics featured in the earlier iteration, pushing voters to rely more heavily on textual summaries.

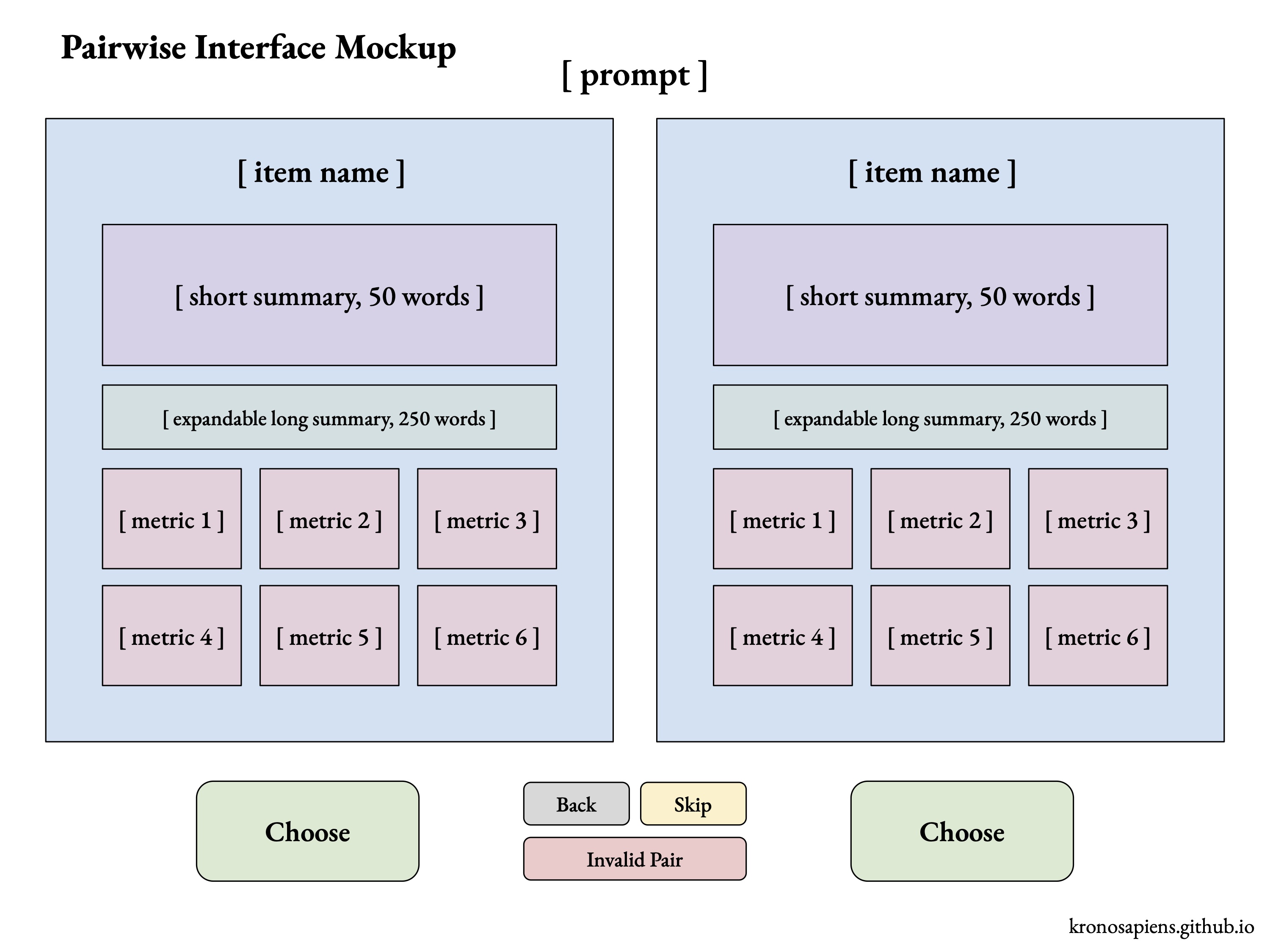

Finally, here is a mockup of an interface I would consider close to ideal, focusing on simplicity and comprehensibility:

This interface leans into ordinal inputs and prioritizes speed and access over gatekeeping, while leveraging AI summarization and metrics to standardize decision framing.

4. Audience Development

The next key consideration when running a pairwise voting process is audience development.

Audience Selection

Pairwise methods are well-suited to the setting of distributed capital allocation by a heterogeneous audience, with many different people coming together to distribute shared resources. They succeed by directing participant attention efficiently over a range of items, without requiring deep prior knowledge of the items in question.

Pairwise methods are less effective when used by a small group of experts, who are more likely to have strong prior knowledge of the items in question. For this audience, who has already performed the cognitive labor of developing opinion, assigning weights directly might be more efficient and more natural.

To give a concrete example, during the Deep Funding pilot a senior Ethereum community member criticized the process on the grounds that they had already formed clear opinions about the right weights for individual projects, and that the pairwise process made it harder to express those opinions.

It is also possible to have an audience which lacks a minimum baseline of context, such that even with a quality interface, they are unable to meaningfully distinguish between items.

The ideal audience, then, is a large and diverse group of people with at least some domain knowledge, able to make judgments on never-before-seen pairs after about 30 seconds of absorbing information. This group will be able to provide the most net information, in terms of both quantity and quality of inputs.

Audience Expectations

Relatedly, it is important that participant expectations be set appropriately.

Pairwise methods don’t ask participants for weights directly, but infer them indirectly using an algorithmic process. For audiences used to assigning values directly, “giving up control” of the weights can be disorienting. After Optimism’s RetroPGF 3, General Magic interviewed participants and found that while participants found the system engaging and an aid in discovery, they also struggled with the shift in expectations of not setting weights directly.

Communicating the behavior of the system, and making the end-to-end process legible for participants, is key to building trust in these methods.

Audience Segmentation

Every voting process needs some way of segmenting and evaluating its participants to prevent vote manipulation. At minimum, this means some form of sybil resistance, whether tokens, identity “passports,” or webs-of-trust built off of pairwise attestation. Choosing the right solution will again be a function of problem and audience.

The dual of sybil resistance is making better use of expert attention through reputation systems. Just as much as we discard fraudulent votes, we can give leverage to experts by assigning their inputs a higher weight. One might imagine a process in which the majority of the community engages early, making a “first pass” over the items, to be followed by expert assessment of only the most ambiguous pairs.

Reputation and identity is a deep field and beyond the scope of this essay, but it is worth gesturing towards how these ideas might be combined.

Audience Compensation

While pairwise voting processes are often seen as more inherently engaging than other forms of voting, it would be naive to expect ongoing voter participation without some external incentive or motivation – financial, relational (status), or both.

Financial rewards are straightforward, but can incentivize mercenary behavior and, being zero-sum, create a drag on resources. Non-financial rewards, such as digital collectibles which double as attestations for a public goods funding reputation system, represent an underexplored and positive-sum alternative.

IV. Continuous Funding

Possibly the most significant application of pairwise methods is the idea of “continuous funding.”

Conventionally, most public goods funding takes place via “rounds.” Each round is a distinct event, featuring a slightly different set of projects and requiring an entirely new set of votes. Putting on a grants round is a large lift, consuming many hours of administrative time on the part of both the sponsoring organization and the projects being considered, and of voting time on the part of participants.

Much of this labor is redundant, as both projects and voters tend to be similar round-over-round. Looking at data from Gitcoin Grant rounds 20 and 22, which took place six months apart in April and November 2024 (disclosure: I participated in both rounds), we see that 52% of the top 25 projects in their “dApps and Apps” category carried over between rounds. If an ecosystem is evolving only 50% between rounds, then the round-based approach is wasting half of both its administrative input and voter attention.

Instead of discrete rounds, which make inefficient use of both administrative and voter inputs, public goods funding should move towards long-lived continuous processes, in which valuable administrative and voter inputs are leveraged over longer periods of time.

Continuous funding processes also allow for a more relaxed attitude towards “correctness,” as the opportunity to course-correct is built in from the get-go. Rather than feel pressured to “get it right” the first time, it becomes possible to “throw something out there” with the confidence that allocations will be updated in response to new information, and that over time the resources will flow towards the point of greatest impact. This “cybernetic” or evolutionary approach to capital allocation – focusing less on static point solutions and more on self-correcting processes – promises to be more robust and resilient than the high-cost, round-based approaches dominant today.

This idea of continuous funding has been explored before, with pilots like GeoWeb’s Streaming Quadratic Funding, and more recently Octant’s StreamVote, combining quadratic voting with Superfluid’s continuous payments infrastructure to distribute funds in real-time.

However, apart from one notable multi-year real-world example, to date no continuous public goods funding process has been built on top of pairwise inputs. For reasons explored below, we believe that pairwise inputs offer a stronger basis for continuous funding, converting scarce attention into actionable allocations at high efficiency.

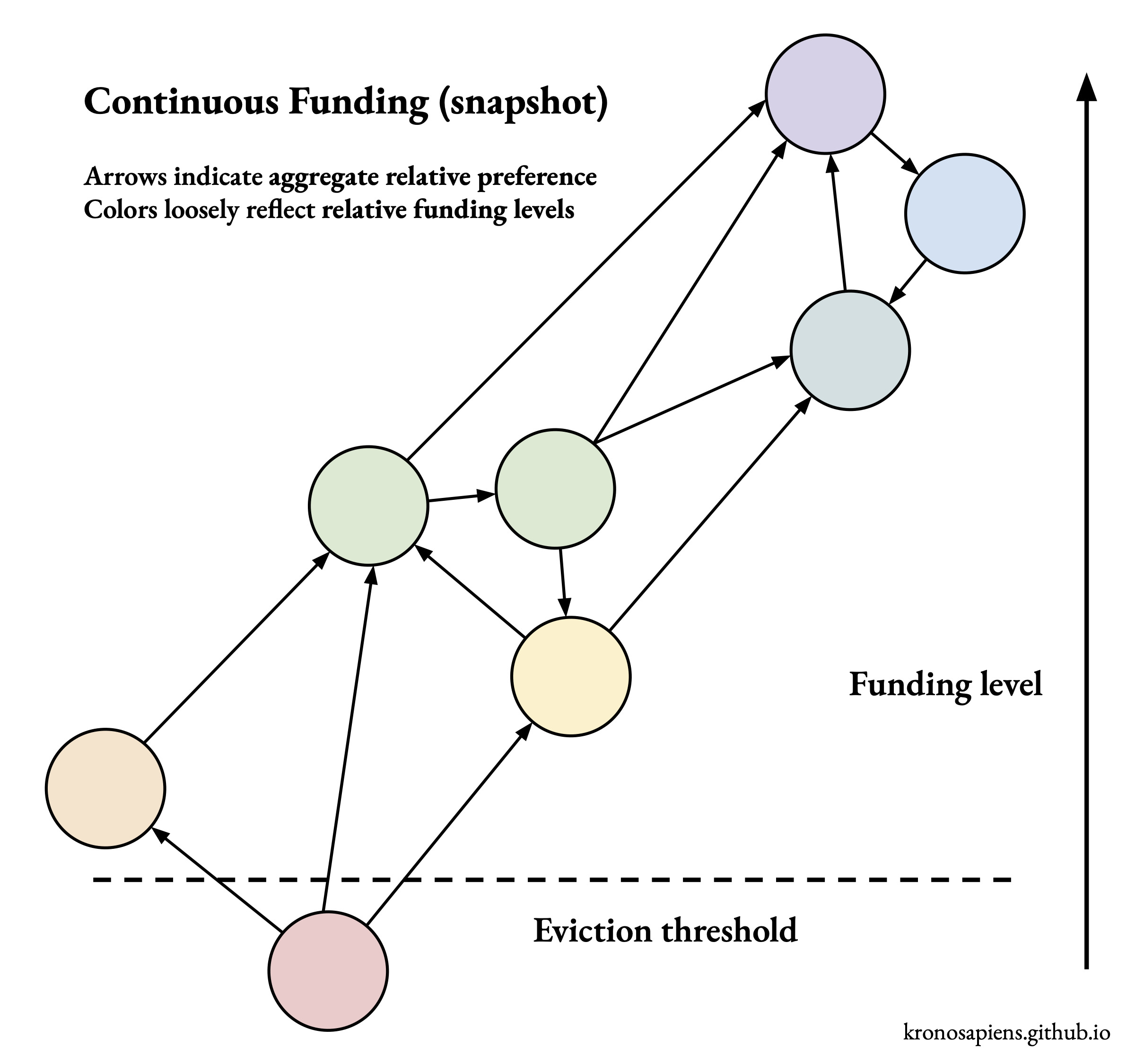

Permissionless Entry

Most public goods funding rounds have high overheads, with staff needed to screen projects, run comms, and audit performance. This high overhead ultimately consumes funds which could otherwise be directed to projects directly, creating inefficiencies which threaten to undermine the legitimacy of the process entirely. A fully permissionless continuous funding process would enable capital allocation at lower cost by reducing or eliminating this overhead.

In a permissionless process, projects add themselves to the pool by putting up a stake. Once in the pool, the active ranking process would surface high-variance new projects, allowing them to quickly “find their level” of funding. Projects that perform poorly – say, more than three standard deviations below the mean – would be evicted from the pool and lose their stake.

See below for a visual intuition for this process:

Pairwise methods are well-suited for this type of permissionless, self-correcting process, due to the logically “self-contained” nature of the pairwise judgment (i.e. a choice of A vs B does not depend on C). In contrast, quadratic “votes” are logically conditioned on the entire set of items (i.e. I might give $10 to A on its own, but only $5 in the presence of B, which gets the other $5), making quadratic methods less naturally adapted to a continuous setting in which items are frequently being added and removed. This limitation creates frictions which must be overcome.

To give a concrete example, StreamVote performed AI screening of projects before allowing them to claim funding, winnowing the final set of projects from 3,980 down to 17 – a 99.6% rejection rate, and large use of administrative power.

In contrast, an always-on pairwise process with active ranking can itself serve to screen and filter a dynamic pool of candidates, eliminating a costly administrative task.

Stale Voting Data

As discussed previously, one of the advantages of pairwise judgments is that they can be meaningfully re-used over time. However, while in theory a vote on a given pair is valid in perpetuity, in practice we should be cautious of relying on stale data. In reality, projects are always evolving, and a preference for A over B may become increasingly inaccurate if A stagnates while B thrives.

One approach to balancing this trade-off is through a decay process in which votes lose their impact over time, perhaps decaying to zero over a two-year period. There are many possible decay curves, all reflecting different assessments of how fast this particular reality changes.

Funding Rates

The complementary question to vote decay is that of “how fast should we distribute the money?” Unlike rounds-based approaches, in which the entire pot is given out at the end of the round, continuous processes must make choices about the speed with which they distribute their funds.

One approach would be to distribute funds at a constant rate over some period of time. A four-year target would see 50% given out after two years, and 100% after four years, at which point the process would end (assuming no new funds).

Another approach, proposed by the Colony team in their 2018 whitepaper, would be to distribute funds at an exponentially decaying rate, such that funds are distributed according to a “half-life.”

A one-year half-life would give out half the funds in the first year, a quarter in the second year, an eighth in the third, and so on (assuming no new funds). Compared to the constant rate, this approach extends the life of the process indefinitely, at the cost of a decreasing funding rate.

Process Tempo

Throughout this section, we have emphasized the value of reducing the administrative overhead involved in running grant rounds. However, we acknowledge that even a continuous process might benefit from a periodic “tempo” of participation. An always-on process is hard to keep top-of-mind, and might see particiption lapse over time.

To counteract this, one could imagine running “campaigns” to periodically refresh voting data at scale, leveraging leaderboards and other incentives to stimulate data-collection. In the best case, resources which would otherwise have gone to administrative tasks can be redirected towards other purposes, such as commissioning compelling digital collectibles to give as rewards to participants.

On the payouts side, one could imagine making payouts on a monthly or quarterly basis, or conditioning payouts on milestones determined by a separate governance process.

The key idea is that user and project experience could be made qualitatively similar to that of a round-based process where it counts, while retaining the benefits of a continuous substrate in which allocations update and distribute in real-time.

V. Evaluation and Legitimacy

At the start of this essay, we argued that the limitations of pass/fail voting led to a shift in interest towards capital allocation. Capital allocation, however, has its own challenges: in particular, evaluation.

As has been well-documented by Metagov’s Grant Innovation Lab, difficulties in evaluating the effectiveness of grant programs are leading to an erosion of trust in public goods funding overall, and a slow reduction in funding for such programs. As a result, over the past year the public goods funding community has increasingly begun prioritizing evaluation over experimentation.

On some level, evaluation is an impossible and fundamentally speculative task. If someone wanted to support public goods and could accurately evaluate the future impact of a present investment (or even the present impact of a past investment), they would be better off making billions on Wall Street and starting a foundation.

Given that nobody is doing that, and that evaluation is on some level made-up, it’s fair to ask what “evaluation” actually achieves. We suggest that evaluation produces legitimacy, which translates concretely into higher future funding inflows. As Vitalik Buterin famously said, “legitimacy is the scarcest resource.”

To adopt ideas from institutional economics, we can imagine evaluation as filling out a currently-barren “policy” layer in the three-layer model of constitution, policy, and operations. In this frame, the “constitutional” layer represents the code, norms, etc., of the grants ecosystem itself, the “policy” layer represents the process by which specific parameters (mechanisms, etc.) are chosen, while the “operational” layer represents the grants rounds themselves: applications, voting, etc. Seen in this way, evaluation is the missing political process needed to bring web3’s public goods funding ecosystem from experiment into maturity.

How might these evaluations be done?

One possibility, adapting techniques used to evaluate large-language models, is to subject allocations themselves to pairwise judgments. In addition to pairwise judgments between projects, the community can make pairwise judgments between allocations produced by competing mechanisms. By comparing the outputs of different allocation processes, a community can set policies for how resources are distributed: this algorithm vs that, this parameterization vs that.

Another possibility, popular in the web3 community, is to lean into “info-finance” as a tool for producing high-quality predictions about the future. Unlike votes, which reflect subjective opinions, financially incentivized predictions can in theory be treated as objectively reliable sources of information. Info-finance is not my area, so I cannot comment deeply on the strengths and weaknesses of this design, but these approaches have always struck me as a touch reflexive, with predictions and allocations influencing each other in complex and hard-to-model ways.

This is not idle speculation. The proliferation of sports betting apps has begun affecting player behavior, who exploit privileged positions to resolve markets in their favor.

Yet another possibility would be to develop new metrics for evaluating the “health” of a funding process. By tracking metrics such as the degree to which a funding distribution follows a power-law, or the churn of projects over time, one can assess how a funding process is performing relative to an idealized baseline.

Whatever approach is used, it is virtually certain that evaluation will become table stakes for those looking to implement capital-allocation schemes.

VI. Additional Considerations

While compelling, pairwise methods have nuances and limits.

The Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives

The “independence of irrelevant alternatives” (IIA) is a key concept in social choice. The principle of IIA says that the relative ranking of two options must never depend on a third (the “irrelevant alternative”). In practice, almost every voting system violates this ideal in some way; the question becomes why and to what degree.

Some pairwise algorithms, such as spectral ranking, intentionally draw in third options to produce richer comparisons with less data. This produces results which reflect a global perspective, incorporating more data but increasing the likelihood of unexpected interactions. This unapologetic rejection of IIA is arguably an advantage in the setting of capital allocation, where the goal is to distribute resources across an entire ecosystem.

However, in high-stakes, single-winner settings like elections, these complex and non-linear interactions can undermine the perceived legitimacy of the process. In those settings, a Condorcet method with stronger guarantees would almost certainly be preferable.

Note: as discussed earlier, individual pairwise judgments are in fact independent of alternatives; it is only the final result which is not.

Intransitivity of Preferences

Closely related to IIA is the idea of cycles and the transitivity of preference – the idea that if you prefer A to B, and B to C, then it is logically consistent that you would prefer A to C. To prefer otherwise creates what is known as a “cycle” of intransitive preferences. For many voting methods, cycles represent contradictions and are seen as inherent flaws.

Spectral methods, on the other hand, handle intransitive preferences naturally – they are not contradictions, but information. Cycles are interpreted naturally as ties, which pose problems for single-winner elections, but not for capital allocation in which funds are simply given out equally.

Further, pairwise spectral methods allow for a different interpretation of intransitivity. Unlike Bradley-Terry, which models every item as having a latent value, and interprets intransitivity as measurement error, spectral methods model intransitivity as a normal part of reality.

To give an example, imagine items A and B, each having qualities X and Y. If we conceptualize voters as making pairwise decisions based on subjective integrations of the data, one voter might integrate X and Y and choose A, while another, filtering through the lens of their own personal beliefs and lived experience, chooses B.

Over hundreds or thousands of voters, the pairwise graph becomes a rich field of relationships with frequent cyclical and intransitive behaviors, reflecting a deep and socially-embedded understanding of the ecosystem in question. Taking this graph as the only knowable ground truth, we then produce weights as a useful synthesis of that data.

One might imagine going even further, devising new metrics for community dynamism based on the degree of intransitivity in a given preference graph – or of treating the preference graph as a type of “constitution” for AI governance. This view of pairwise data – not as messy and needing of discipline – but as rich and nuanced truth, invites bold new visions.

Dealing with Heterogeneity

One of the few prerequisites to using pairwise techniques is making sure that the items being compared are meaningfully comparable. This may sound tautological – but it is by no means guaranteed. To give an example, one can meaningfully prefer an apple or an orange; one cannot meaningfully prefer an apple to the color orange.

Part of the practitioner’s skill is ensuring that the items being considered are part of a semantically coherent set. This meaning can come from either grouping like items together, or framing the comparison in a way which makes sense for the given set.

To give a concrete example, this year’s Deep Funding initiative framed the decision in terms of the relative impact of two software dependencies on a given software project; the same dependency might be assessed very differently depending on which project’s context was being considered.

This idea can be extended to the case when projects are of the same type, but have different funding needs – by framing the question in terms of “where should we direct the next marginal dollar,” projects of different scales can be meaningfully considered as part of the same set.

In permissionless settings where it may be difficult to ensure homogeneity in advance, techniques like star grouping can be used to segment items into coherent sets on-the-fly.

VII. Putting It All Together

As argued in the introduction, pairwise methods should be understood not as a single technique or mechanism, but as a paradigm of social choice. Having introduced the various pieces of this paradigm, we can begin putting them together, and offer concrete estimates of the actual attention requirements for public goods funding.

Assuming 30 seconds per vote and 10 votes per item with active ranking, pairwise methods can produce allocations at an attentional cost of 5 minutes per item. For a set of 600 items, this calls for 50 hours of total voter attention. If we assume each voter contributes four five-minute sessions (20 minutes), then we need only 150 voters to produce legitimate results – a relatively easy lift.

As a continuous process, things get even better. If we assume that only ~25% of the items undergo meaningful change in a given quarter, we can sustain a continuous funding process indefinitely with an attention cost of 5 minutes per item per year.

Further, given a sufficiently robust reputation system, we could imagine running seasonal “campaigns” in which the community contributes en masse to project filtering, followed by experts who resolve the highest-ambiguity pairs or adjudicate between the outputs of funding mechanisms themselves. Participants could be rewarded with sought-after digital collectibles, serving as reputation attestations and cultivating a public-spirited group identity.

The net effect is that of an always-on social choice “sensor” – a solar panel for governance – collecting ambient preference information and converting it into actionable outputs in real-time.

The idea of sustaining a complex public goods funding ecosystem with so little effort might seem implausible, and the continued development of these techniques will certainly surface new challenges and limitations. And yet, the arguments have been laid out, and these are the conclusions we’ve drawn.

Final Thoughts

The task of helping groups of people effectively manage shared resources is one of the most pressing problems of our day. We have argued that pairwise methods, seen not as isolated techniques but as part of a paradigm of social choice, offer a compelling toolkit for solving exactly this problem.

Relative to other techniques and to their underlying potential, pairwise methods remain underexplored. By articulating a “pairwise paradigm,” we hope to help chart the way.