Exploring Deep Funding's Jury Data

This analysis explores 611 pairwise judgments from 51 jurors evaluating Ethereum dependencies through the Deep Funding experiment.

Key findings:

- Pairwise evaluations show 89% agreement when comparing diverse projects, and 63% for similar.

- Contrary to intuition, longer thinking times did not improve decision quality.

- Results suggest pairwise methods are ready for greater deployment in public goods funding.

I. Introduction

Last winter, an exciting experiment emerged from the Ethereum public-goods-funding ecosystem. With a $200k prize pool put up by Vitalik himself, a group of enthusiasts began working on a novel method for supporting public goods: using AI agents to generate funding proposals, and using human inputs to adjudicate between them. “AI as the engine, humans as the steering wheel” became the initiative’s rallying cry.

The project, known as Deep Funding, aimed to develop “impact weights” for ~30 first-order Ethereum dependencies (clients, languages, developer tools), and ~5,000 of their child dependencies. With these weights in hand, funding could be “flowed” through the Ethereum ecosystem, supporting dependencies which might otherwise have gone under-funded.

A key part of the design involved collecting jury data – the critical inputs used to decide which AI proposals were most accurate and how to combine them. Rather than asking jurors to rank entire lists of dependencies, the design called for pairwise comparisons: assessing the relative impact of just two dependencies at a time. This pairwise format would simplify the human judgment task – instead of having to determine a full set of (meaningful) weights across dozens dependencies, they could focus their valuable attention on just one pair at a time.

A friend brought the project to my attention in December, and – having done a fair amount of work with pairwise methods – I was intrigued. I began volunteering, helping to refine the project design and the pairwise juror flow.

Over the course of this past winter and spring, Deep Funding gathered jury data using Pairwise, the voting tool developed by General Magic partially based on my own past work with Colony. Over this time period, 51 jurors provided 611 votes on project pairs across both the primary and secondary dependencies.

This analysis will explore these data, with the aim of better understanding both the dependency relationships, and the performance of the underlying pairwise process itself. On a personal note, I have been enthusiastic about these methods for years, and am happy to see them increasingly embraced by the Ethereum public-goods community.

II. Data Analysis

Our analysis will proceed in three steps:

-

First, we will discuss the basics of the data set and our metrics of interest.

-

Second, we will explore the judgments overall, looking at the degree to which jurors could distinguish between projects as well as the agreement among jurors.

-

Third, we will look at the specific relationship between thinking times and juror judgments, looking to understand whether more time spent per-pair produced better results.

Analysis code can be found here. The data itself are not yet public.

Preliminaries

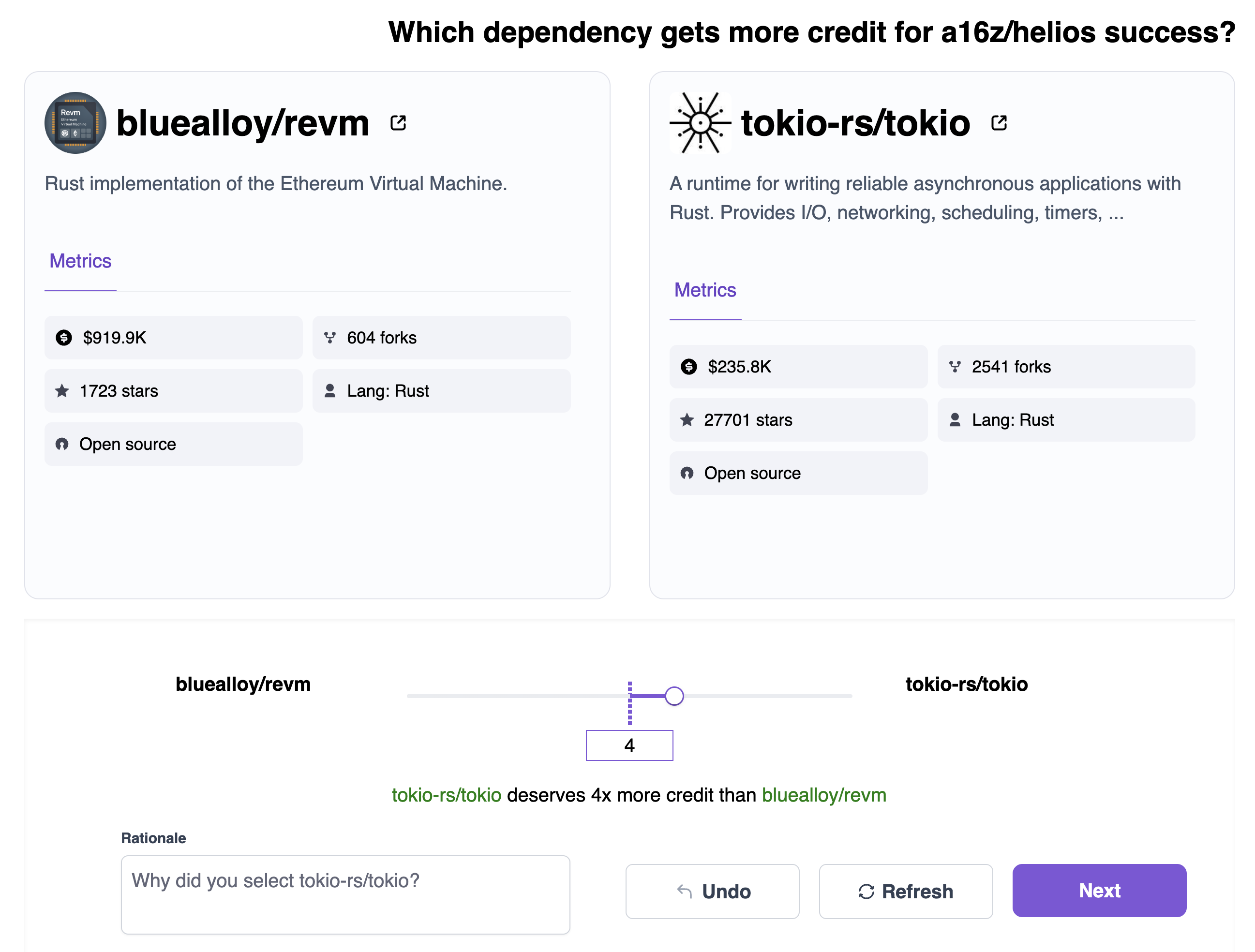

The data includes 611 pairwise juror judgments gathered between December 24, 2024 and March 31, 2025. Participating jurors were presented with pairs of projects through the Pairwise interface:

The projects were organized into two data sets. The first, “Level 1,” consists of Ethereum’s direct dependencies – representing critical Ethereum-specific infrastructure. For L1, 30 jurors provided 402 votes over 35 unique projects, with an average of 13 votes per juror.

The second, “Level 3,” consists of the child dependencies of the L1 projects – representing general software development dependencies. For L3, 21 jurors provided 209 votes over 144 unique projects, with an average of 9 votes per juror.

These twin datasets permit a unique exploration: by performing the same analysis on both sets, we can learn not only what the data tell us about the Ethereum ecosystem, but better understand the pairwise method itself by seeing how the results differ between sets. A pairwise meta-analysis, if you will.

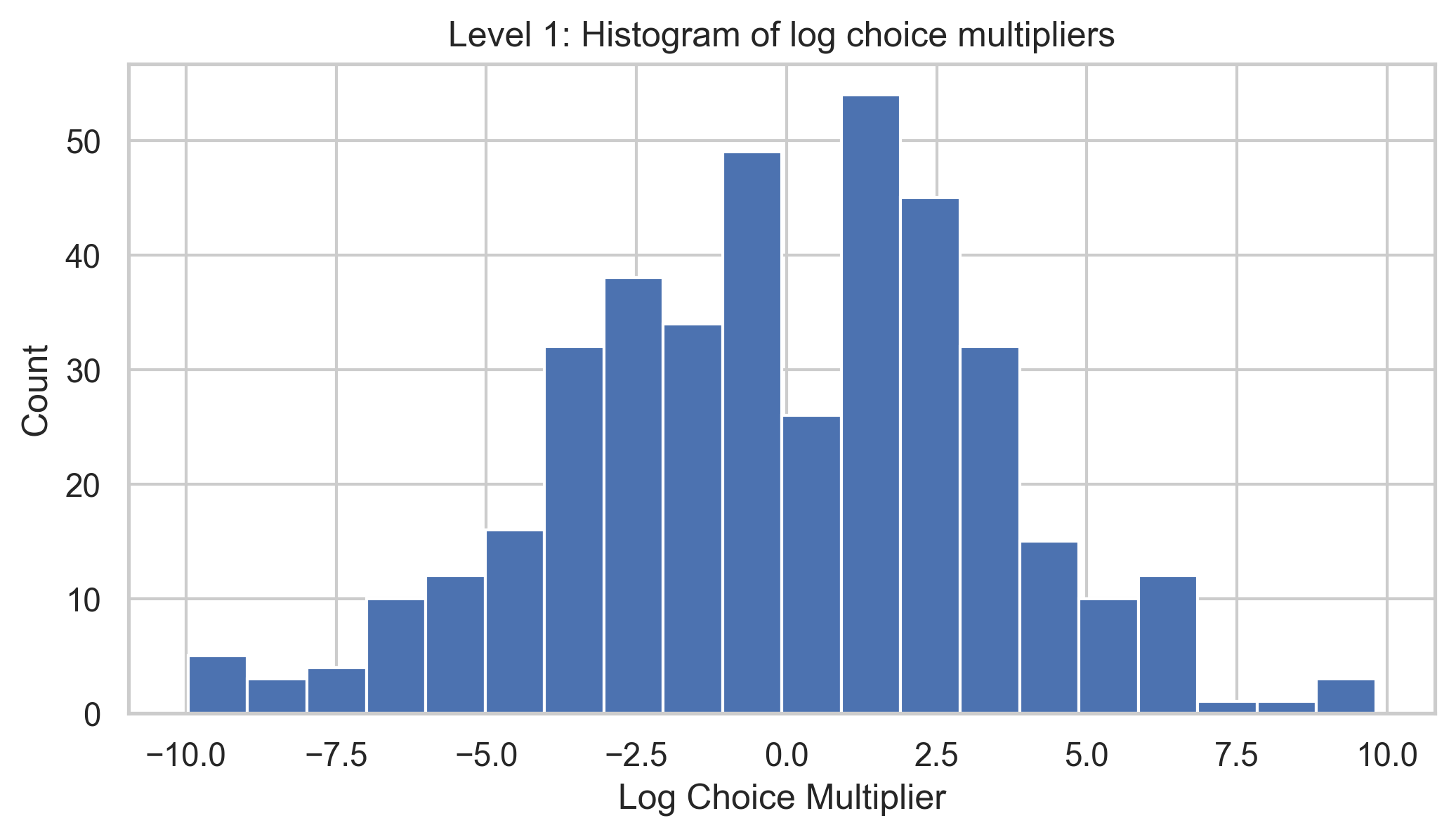

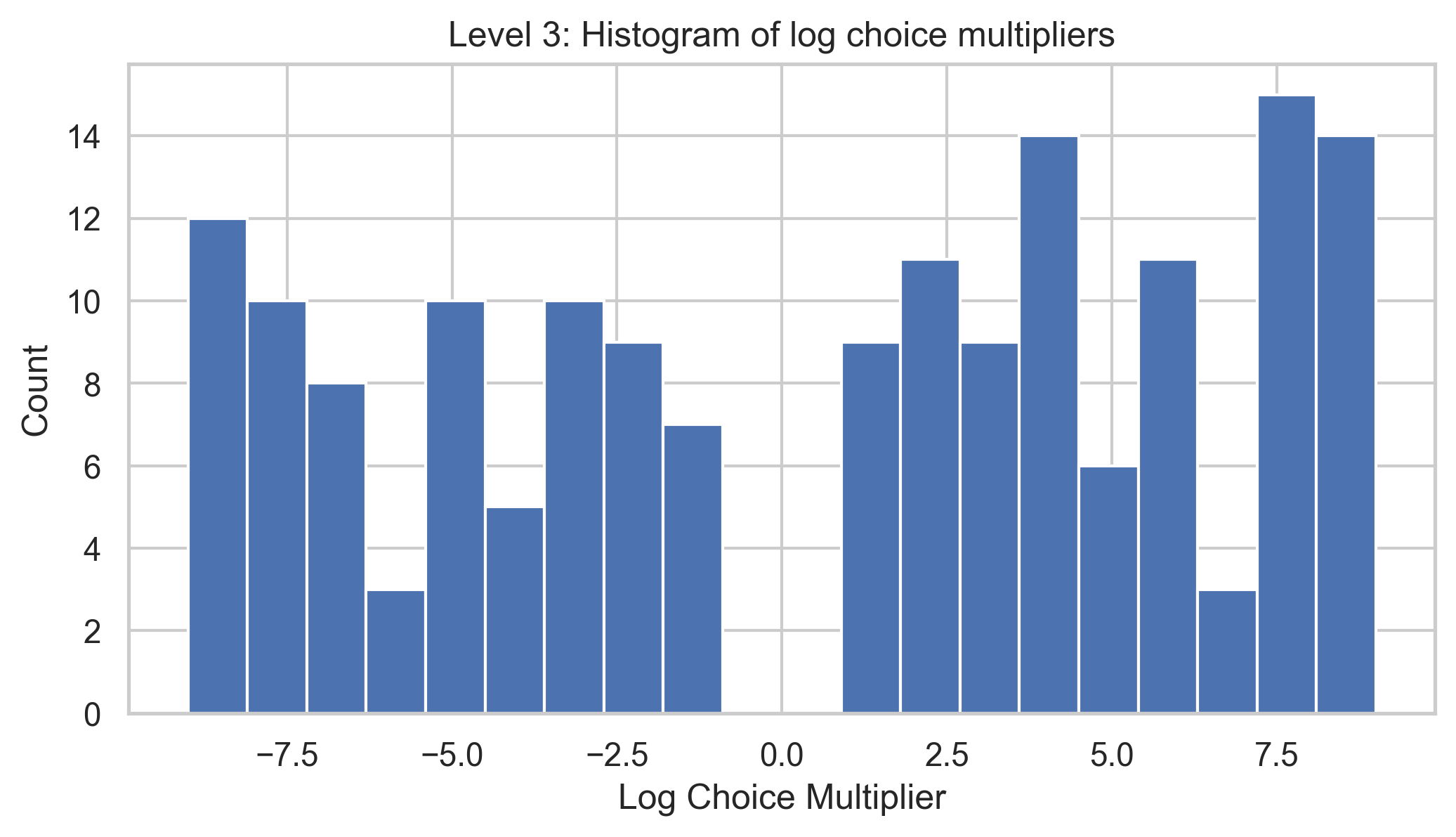

As part of the data processing, we introduce a few additional fields. The first is the log multiplier – the log2 of the multiplier (given between 1 and 1024), used to simplify data visualization. The second is the choice multiplier – the same multiplier but made positive or negative based on which project was chosen, enabling direct comparison between jurors. The third is the thinking time – the difference in timestamps between sequential votes by the same juror.

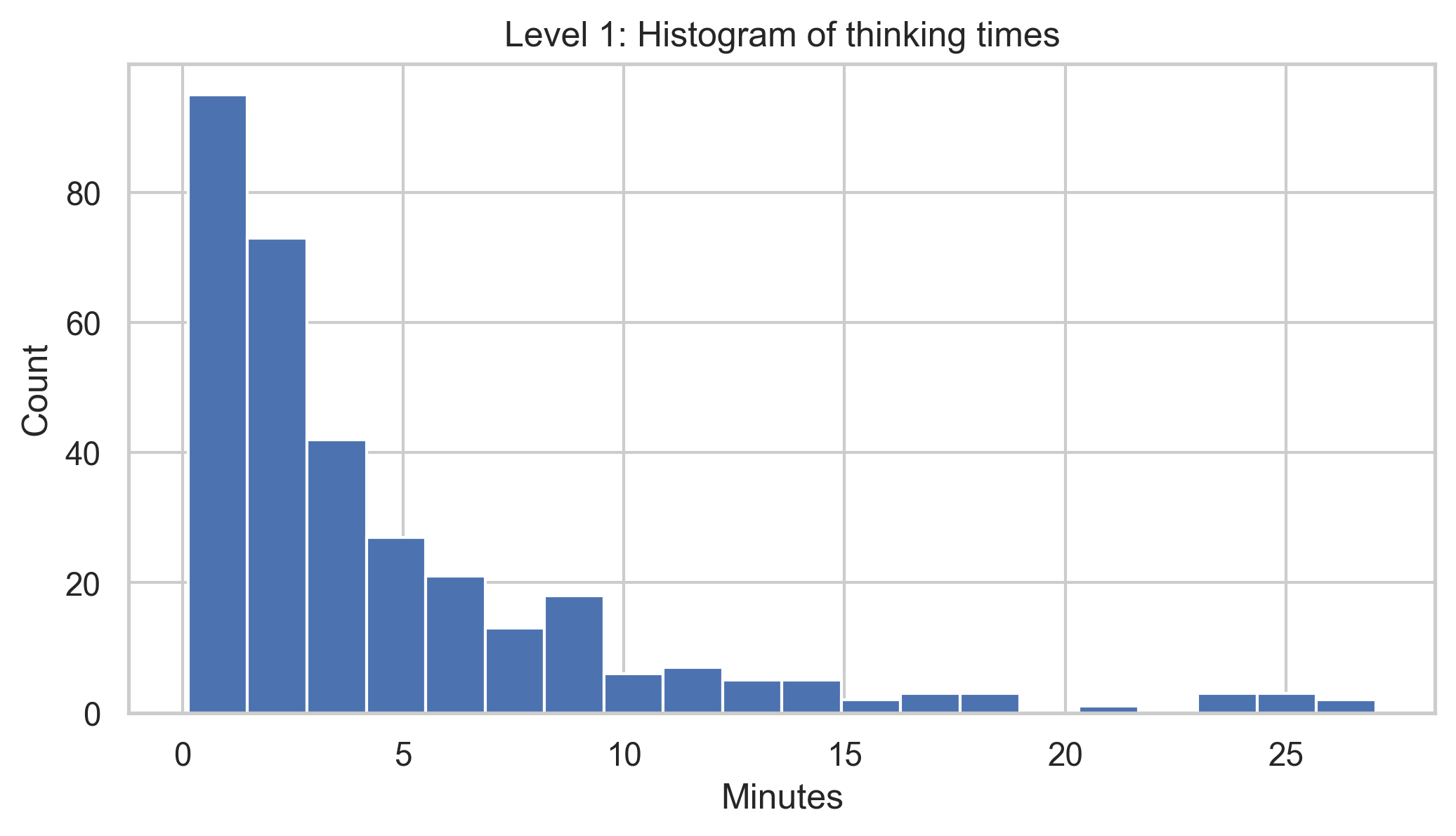

Methodological note: thinking time is inferred from the time elapsed between votes and should be considered a noisy signal. Further, some of the duration is explained by typing time, correlating with the length of the rationale string by .41 in L1 and .19 in L3.

Overall Juror Assessments

The first thing we look at is the distribution of multipliers given by the jurors. These histograms count the individual juror votes, grouped by the strength of the given multipliers. We see that for L1, the multipliers cluster more closely around 0, likely reflecting the consistent quality of all projects in the set. Given that L1 consists of Ethereum’s primary dependencies, it is unlikely that one would be significantly more important than another, and the data reflect this.

For L3, we see a skew towards higher multipliers, reflecting the greater variance in dependency impact and relevance. Given that L3 projects can run the gamut from critical dependencies to shell scripting utilities, it is unsurprising that the relative impact would be larger.

Overall, these data align with our intuition that the delta between L1 dependencies should generally be smaller than that between L3 dependencies.

Let’s look at the mean and standard deviation of the multipliers given by jurors for project pairs. These scatter plots show individual project pairs, presenting the mean and standard deviation of all juror votes on that particular pair.

We see that for L1, the standard deviation is relatively constant, indicating that the level of agreement among jurors was similar across the entire data set. Looking at L3, we see a very different effect: the standard deviation decreases at the extremes and increases towards the center, suggesting that larger differences in impact were easier to distinguish – an intuitive result.

It is worth noting that the average standard deviation for L1 is higher than that of the obvious cases in L3, suggesting that while L1 comparisons were more uniform in difficulty, they were on the whole more difficult than the simplest cases in L3.

If we ignore the multipliers and limit our sense of “agreement” to project choice, then jurors in L1 agreed with each other 63% of the time (based on 60 pairs receiving exactly two votes), while in L3 they agreed with each other 89% of the time (based on 28 pairs receiving exactly two votes). This suggests that the pairwise process captured meaningful signal, and that the signal was more clear in L3 than L1.

Juror Thinking Times

A major debate during the Deep Funding design process concerned the length of time jurors should spend thinking about each pair. Opinions ranged from as little as five or ten seconds per pair, all the way to five or even ten minutes. This 60-fold gap in expectations is striking, and suggests a practice guided more by intuition than empirical analysis. What do the data show?

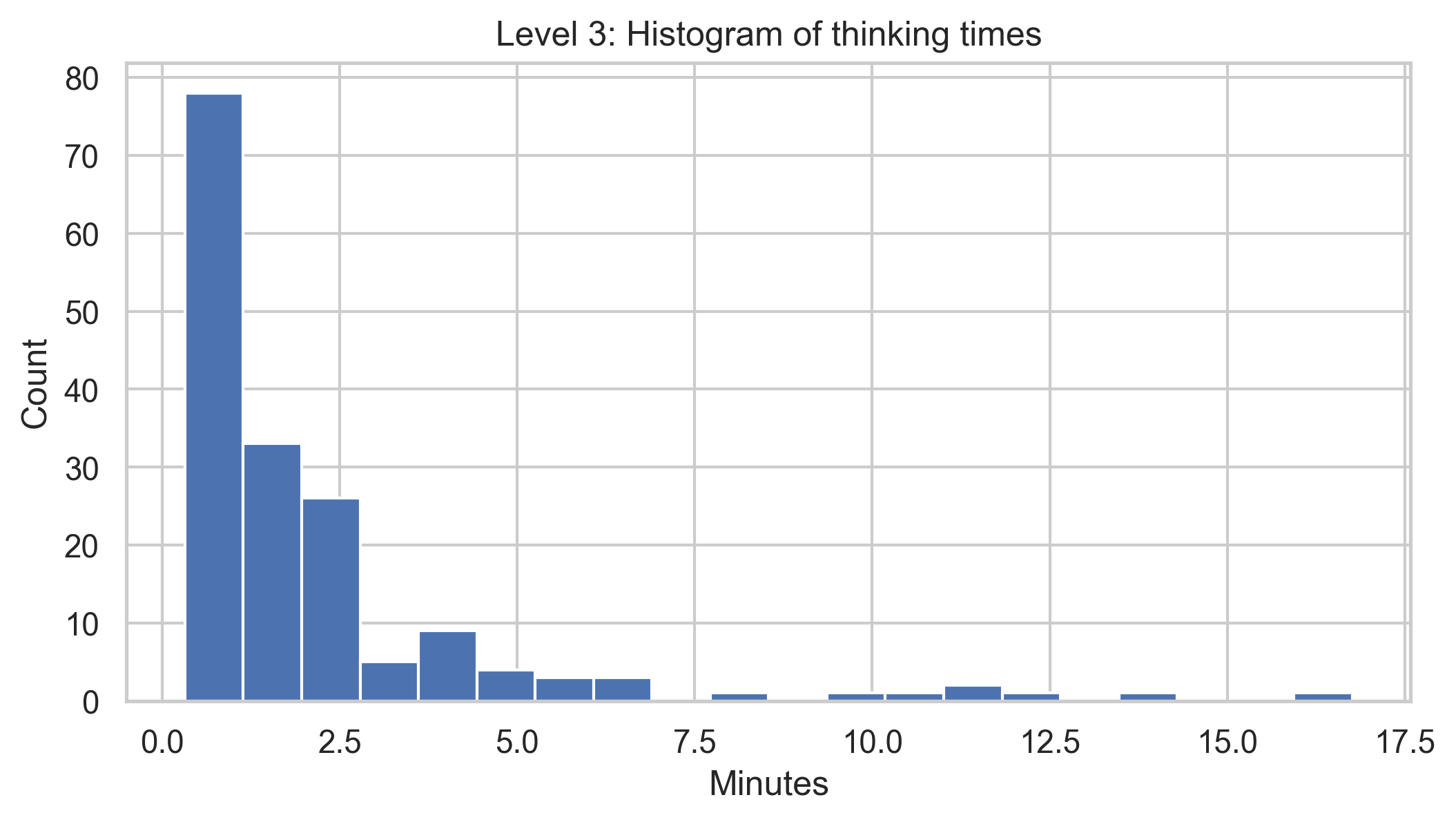

Among L1 jurors, the median thinking time was 2.8 minutes, and among L3 jurors, 1.3 minutes. This makes sense, as L3 projects have greater variety, and so should be generally easier to distinguish.

One might wonder whether jurors who spent more time thinking would be more discerning; perhaps longer thinking times correlated with higher (or lower) multipliers. Looking at the L1 plot of thinking times vs. final judgments, we see no correlation. Looking at the same plot for L3, we see a small but weak positive correlation.

This next plot (my personal favorite) shows both votes for every project pair which received exactly two votes and where both votes had valid thinking times. We draw every project pair’s votes in the same color, and connect them with a dotted line. The slope of the line tells us how the longer-thinking juror’s vote differed from their shorter-thinking counterpart.

While dense with information, this chart offers a fine-grained view of voting behavior and suggests an interesting dynamic. Overall, in L1 it seems that more thinking time rarely resulted in a very different assessment of impact, and when it did, the effect seemed random. In contrast, in L3 it seems as though more time thinking typically resulted in a smaller multiplier – and only rarely in a choice change.

III. Conclusion

Overall, the data suggest that the pairwise process is useful for gathering subjective assessments of relative impact at scale.

The data on overall assessments confirms our intuition that it is easier to distinguish between things that are different than things which are similar. Not only was the perceived relative impact higher in L3, where projects vary more in quality, but the level of agreement was higher – suggesting that the decision problem was easier overall. The 89% agreement among jurors in L3 is striking and seems to pave the way for deployments at greater scale.

The data on thinking times challenges our intuition that more time spent thinking would produce better results. With the caveat that our thinking times are a noisy signal, we see little evidence that longer thinking times result in meaningfully better decisions. If anything, the data suggest the opposite – that we should be encouraging jurors to make more, faster decisions rather than fewer, slow ones.

Despite their promise, pairwise methods are relatively underdeveloped. There is ample room for research into improved UI, more efficient pair selection, and continuous funding paradigms in which juror votes are required only marginally instead of en masse. Through these continued investigations, pairwise methods have the potential to become critical infrastructure for Ethereum public goods funding – proving that sometimes the best way to understand a system is by building tools to evaluate it.