Setting up Unit Tests with Flask, SQLAlchemy, and Postgres

Moving forward with the development of the ParagonMeasure web application, it’s come time to set up the database and configure the test suite to transact/rollback test data.

Setting up a Postgres database was surprisingly easy; there’s a simple tutorial which worked exactly as expected.

Setting up the database to work with my tests, however, was a different story. I tried creating ‘setUp’ and ‘tearDown’ functions to create and drop tables according to my schema, but found that Postgres would flat-out lock whenever I tried tried to call db.drop_all(). No error, just a complete freeze until I shut down the entire Postgres server.

Some investigation turned up some evidence suggesting that this is not uncommon behavior with Postgres – attempting to drop tables can cause Postgres to lock, if there happen to be any outstanding connections.

Of course, coming from the Candyland of Rails, I’d never had to work with databases at this level before (db.drop_tables was a common and casual activity). This was a new challenge, but one I was determined to solve.

Engines, Connections, DBAPIs

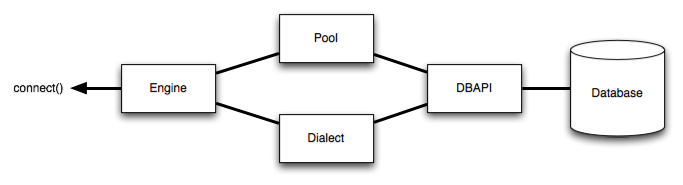

First steps were getting a better handle on the under-the-hood workings of both SQLAlchemy and SQLAlchemy-Flask, the libraries I was using to mediate between Flask and my database. The SQLAlchemy docs on sessions and engine configuration were very helpful, providing useful diagrams like this:

Reading through the docs, I learned some useful terms:

DBAPI: a low-level protocol for interacting with a database; not something that I would use, but something that an ORM library would use at the lower levels.

Engine: an object which manages connections to the database. Given that a database is designed to be accessed by many, many computers at once, engines are used to control and manage the database’s resources and DBAPI connections. Engines are able to give connections to the database to other objects. In general, one engine is created once when an application is initialized, and stays alive for the duration of the application.

Session: the abstraction layer most suitable for my purposes. A session represents a series of transactions with a database, as well as holds all objects that have not yet been written to the database. A session then represents a kind of “staging area” where my application can add and manipulate objects before “flushing” the entire thing to the database in a series of optimized SQL statements. I believe that sessions are generally created and destroyed during the life of an application, as needed, requesting a connection from the engine, which persists.

Sessionmaker: A factory object for creating sessions. Similar to an engine, this object is created once when an application is first instantiated (part of the application’s configuration), and persists in memory, creating new sessions as needed. In SQLAlchemy, a sessionmaker is instantiated by passing an engine as an argument, which should suggest the connection between those two objects:

Session = sessionmaker(bind=some_engine)

session = Session()Here, Session is a factory class created by calling sessionmaker bound to some_engine. session is an individual session object, created by instantiating the Session() class.

It seemed that, for my purposes of controlling the database, I would be fine sticking with the default engine, and focusing on learning about sessions.

Flask and SQLAlchemy

Another challenge was figuring out how to balance between SQLAlchemy and Flask-SQLAlchemy. The former is the robust ORM library suitable for any Python project, while the latter is a Flask extension designed to facilitate using SQLAlchemy in Flask. I wanted to find an elegant solution that took advantage of both APIs and used the Flask-SQLAlchemy API whenever possible, so I wanted to figure out how they were connected.

Popping into the terminal, I did some investigation.

Here’s a snippet from my webapp.__init__:

from flask import Flask

from flask.ext.sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config.from_object('webapp.config.Development')

db = SQLAlchemy(app)And so in my terminal:

In [2]: webapp.db

Out[2]: <SQLAlchemy engine='postgresql://kronosapiens:apple@localhost/pm_webapp'>

In [3]: webapp.db?

# A lot of stuff, including:

File: /Users/kronosapiens/Dropbox/Documents/Development/code/environments/pm/lib/python2.7/site-packages/flask_sqlalchemy/__init__.pyOk, so db in this case is part of Flask-SQLAlchemy, not SQLAlchemy proper. Good to know; this is a good sign. Digging further:

In [4]: webapp.db.session # Tab completion

webapp.db.session webapp.db.sessionmaker

In [5]: webapp.db.session

Out[5]: <sqlalchemy.orm.scoping.scoped_session at 0x10c4a5990>

In [6]: webapp.db.session?

# A bunch more stuff, including:

File: /Users/kronosapiens/Dropbox/Documents/Development/code/environments/pm/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sqlalchemy/orm/scoping.pyAlright, it seems that I’ve crossed over into SQLAlchemy land. My hunch would be that Flask-SQLAlchemy subclassed the db object and added some Flask-specific features, which is why it contains methods and attributes from regular SQLAlchemy. Open source is fun.

Understanding Transactions

I knew my testing problem was something to do with transactions – I was starting them, but for whatever reason not finishing them up properly.

Reading the SQLAlchemy session docs, I arrived at the idea of ‘object states’. There are four possible states an object can be in, within a session:

- Transient – created, within the session, but not yet saved to the database.

- Pending – an object added to the session using the

add()method. - Persistent – an object both in the session and saved to the database.

- Detached – an object in the database, but not a part of any session.

Understanding these distinctions was super helpful in understanding the role and behavior of sessions. Consider the following terminal session:

In [7]: daniel = Participant('daniel')

In [8]: daniel

Out[8]: <Participant 'daniel'>

In [9]: from sqlalchemy import inspect

In [10]: insp = inspect(daniel)

In [11]: insp.transient

Out[11]: True

In [12]: insp.pending

Out[12]: False

In [13]: webapp.db.session.add(daniel)

In [14]: insp.transient

Out[14]: False

In [15]: insp.pending

Out[15]: True

In [16]: webapp.db.session.rollback()

2014-07-29 18:02:22,971 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine ROLLBACK

In [17]: insp.pending

Out[17]: False

In [18]: insp.transient

Out[18]: TrueWell, at least something makes sense. Moving on.

Well, wait a second – might we be able to use webapp.db.session.rollback() to restore our database after each test? Let’s try:

In [1]: from webapp.models import *

In [2]: from webapp import db

In [3]: db

Out[3]: <SQLAlchemy engine='postgresql://kronosapiens:apple@localhost/pm_webapp'>

In [4]: Participant

Out[4]: webapp.models.Participant

In [5]: Participant.query.all()

# Suppressing SQL > stdout output some more

Out[5]: [<Participant u'test'>]

In [6]: daniel = Participant('daniel')

In [7]: db.session

Out[7]: <sqlalchemy.orm.scoping.scoped_session at 0x107b49690>

In [8]: db.session.add(daniel)

In [9]: Participant.query.all()

Out[9]: [<Participant u'test'>]

In [10]: db.session.commit()

In [11]: Participant.query.all()

Out[11]: [<Participant u'test'>, <Participant u'daniel'>]

In [12]: db.session.rollback()

In [13]: Participant.query.all()

Out[13]: [<Participant u'test'>, <Participant u'daniel'>]Darn. I was hoping that I wouldn’t show up in those results.

Alright, so it seems that webapp.db.session.rollback() can reset the session, but can’t do much once we’ve flushed the session to the database. Also good to know.

This webapp.db.session object seems to have a lot of goodies. Let’s see what else it can do:

In [132]: webapp.db.session. # Tab completion

webapp.db.session.add webapp.db.session.connection webapp.db.session.get_bind webapp.db.session.query

webapp.db.session.add_all webapp.db.session.delete webapp.db.session.identity_key webapp.db.session.query_property

webapp.db.session.autoflush webapp.db.session.deleted webapp.db.session.identity_map webapp.db.session.refresh

webapp.db.session.begin webapp.db.session.dirty webapp.db.session.info webapp.db.session.registry

webapp.db.session.begin_nested webapp.db.session.execute webapp.db.session.is_active webapp.db.session.remove

webapp.db.session.bind webapp.db.session.expire webapp.db.session.is_modified webapp.db.session.rollback

webapp.db.session.close webapp.db.session.expire_all webapp.db.session.merge webapp.db.session.scalar

webapp.db.session.close_all webapp.db.session.expunge webapp.db.session.new webapp.db.session.session_factory

webapp.db.session.commit webapp.db.session.expunge_all webapp.db.session.no_autoflush

webapp.db.session.configure webapp.db.session.flush webapp.db.session.object_sessionNeat. And look at that – .close() and .close_all(). Those look like they might be able to solve our Postgres locking problem. Let’s see what they do, through a little example:

In [33]: daniel

Out[33]: <Participant 'daniel'>

In [34]: webapp.db.session.add(daniel)

In [35]: webapp.db.session.commit()

# I have Flask-SQLAlchemy set to print all queries to stdout

2014-07-29 18:21:52,522 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine BEGIN (implicit)

2014-07-29 18:21:52,522 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine INSERT INTO participant (name) VALUES (%(name)s) RETURNING participant.id

2014-07-29 18:21:52,522 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {'name': 'daniel'}

2014-07-29 18:21:52,526 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine COMMIT

In [36]: Participant.query.all()

2014-07-29 18:22:05,772 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine BEGIN (implicit)

2014-07-29 18:22:05,772 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine SELECT participant.id AS participant_id, participant.name AS participant_name

FROM participant

2014-07-29 18:22:05,772 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {}

Out[36]: [<Participant u'daniel'>]

In [37]: insp.persistent

Out[137]: TrueVery cool. I saved myself to the database, and retrieved myself using the .query.all() method that my Participant model inherited from db.Model.

Now let’s try dropping the table (fingers crossed):

In [138]: webapp.db.drop_all()

2014-07-29 18:25:49,958 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine select relname from pg_class c join pg_namespace n on n.oid=c.relnamespace where n.nspname=current_schema() and relname=%(name)s

2014-07-29 18:25:49,958 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {'name': u'session'}

2014-07-29 18:25:49,963 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine select relname from pg_class c join pg_namespace n on n.oid=c.relnamespace where n.nspname=current_schema() and relname=%(name)s

2014-07-29 18:25:49,963 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {'name': u'participant'}

2014-07-29 18:25:49,965 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine

DROP TABLE session

2014-07-29 18:25:49,965 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {}

# ?? Looks like it's locked.

^C^C^C^C^C^C^C^C^C^C^C

# Yep. Very locked.Alright, time to restart Postgres… let’s try this again.

In [1]: import webapp

In [2]: from webapp.models import Participant

In [3]: daniel = Participant('daniel')

In [4]: from sqlalchemy import inspect

In [5]: insp = inspect(daniel)

In [6]: insp.transient

Out[6]: True

In [7]: webapp.db.session.add(daniel)

In [8]: insp.transient

Out[8]: False

In [9]: Participant.query.all()

# Suppressing the SQL Query > stdout for brevity

Out[9]: []

In [10]: webapp.db.session.commit()

# Suppressing the SQL Query > stdout for brevity

In [11]: Participant.query.all()

# Suppressing the SQL Query > stdout for brevity

Out[12]: [<Participant u'daniel'>]

In [12]: webapp.db.session.close()

2014-07-29 20:14:06,950 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine ROLLBACK

In [13]: webapp.db.drop_all()

2014-07-29 20:14:17,811 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine select relname from pg_class c join pg_namespace n on n.oid=c.relnamespace where n.nspname=current_schema() and relname=%(name)s

2014-07-29 20:14:17,812 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {'name': u'session'}

2014-07-29 20:14:17,815 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine select relname from pg_class c join pg_namespace n on n.oid=c.relnamespace where n.nspname=current_schema() and relname=%(name)s

2014-07-29 20:14:17,815 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {'name': u'participant'}

2014-07-29 20:14:17,817 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine

DROP TABLE session

2014-07-29 20:14:17,817 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {}

2014-07-29 20:14:17,821 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine COMMIT

2014-07-29 20:14:17,825 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine

DROP TABLE participant

2014-07-29 20:14:17,826 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine {}

2014-07-29 20:14:17,835 INFO sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine COMMIT

In [14]:SUCCESS!!! It seems like all that was missing was a call to the session telling it to close the connection.

Back to the Point: Unit Tests

Let’s make some changes to our test file and see what we’ve got:

import pdb # pdb.set_trace()

import unittest

import random

from webapp import app, db

from webapp.models import Participant, Session

class TestParticipant(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

app.config.from_object('webapp.config.Testing')

db.session.close()

db.drop_all()

db.create_all()

def test_lookup(self):

participant = Participant('test')

db.session.add(participant)

db.session.commit()

participants = Participant.query.all()

assert participant in participants

print "NUMBER OF ENTRIES:"

print len(participants)Now, I’m sure there are better ways to write this test file – I struggle with writing test files (although not the tests themselves), because I’m always struggling to balance the desire to keep the code DRY, to keep the tests fast, and to ensure that they’re adequately rigorous. It seems like one of those “pick two of three” situations. Anyway, the subject for another post.

I’m very sure, though, that my database is getting wiped between each test. I know this because the last line of the test prints 1, even if I run the test over and over again.

And there you have it. I’ve gotten my test suite to wipe the database between each test. Rigorous testing, here we come.

As an aside, I wonder if this “Postgres locking” situation is worth making a pull request… open source contributor, here I come.

– Update – Database troubles aren’t over – if you find yourself struggling with an error like this:

E InternalError: (InternalError) cannot drop table "group" because other objects depend on it

E DETAIL: constraint trial_groups_group_id_fkey on table trial_groups depends on table "group"

E HINT: Use DROP ... CASCADE to drop the dependent objects too.

E '\nDROP TABLE "group"' {}There’s a great blog post addressing the issue here.

– Update 2 –

Apparently session.close() wasn’t my only option. Compare with session.remove()

In [13]: db.session.close?

Type: instancemethod

String form: <bound method scoped_session.do of <sqlalchemy.orm.scoping.scoped_session object at 0x10438b0d0>>

File: /Users/kronosapiens/Dropbox/Documents/Development/code/environments/pm/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sqlalchemy/orm/scoping.py

Definition: db.session.close(self, *args, **kwargs)

Docstring: <no docstring>

In [14]: db.session.remove?

Type: instancemethod

String form: <bound method scoped_session.remove of <sqlalchemy.orm.scoping.scoped_session object at 0x10438b0d0>>

File: /Users/kronosapiens/Dropbox/Documents/Development/code/environments/pm/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sqlalchemy/orm/scoping.py

Definition: db.session.remove(self)

Docstring:

Dispose of the current :class:`.Session`, if present.

This will first call :meth:`.Session.close` method

on the current :class:`.Session`, which releases any existing

transactional/connection resources still being held; transactions

specifically are rolled back. The :class:`.Session` is then

discarded. Upon next usage within the same scope,

the :class:`.scoped_session` will produce a new

:class:`.Session` object.