Mimicking DCI through Integration Tests

DCI, or Data, Context, and Interaction, is a programming paradigm primarily developed by Trygve Reenskaug and James O. Coplien in which code is organized by object role in addition to being organized by class. Considered by some to be an evolution of the object-oriented programming paradigm, DCI strives to address a percieved shortcoming of Object-Orientation, namely, that organizing behavior by class (unit) does nothing to inform a developer how the code will be executed at runtime, once multiple objects have been instantiated and are busily interacting with each other.

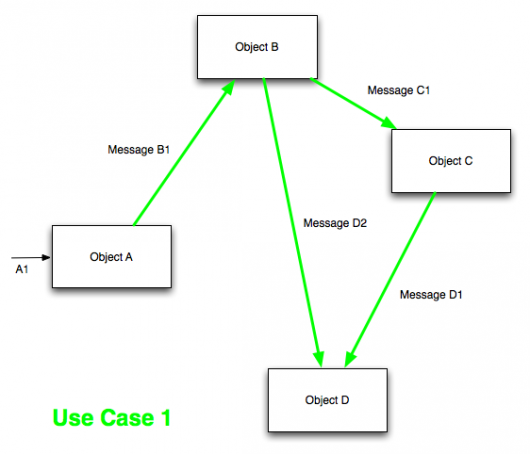

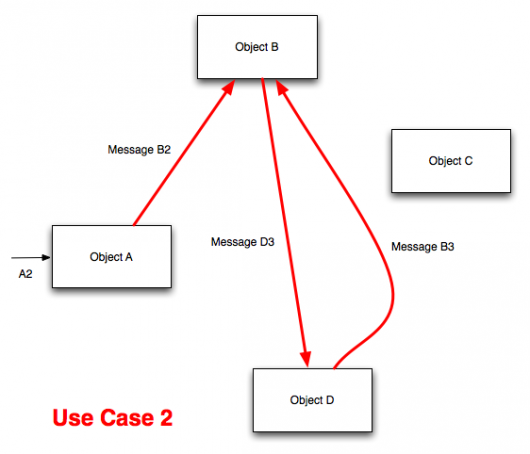

In his post on DCI, Victor Savkin provides two diagrams to illustrate this problem.

Looking at these diagrams, it becomes clear that while both use cases are making use of the same models, they involve completely different interactions. Therefore, an analysis undertaken only of the models and their methods will not help a developer understand what will actually take place at runtime.

The solution to this problem encapsulated by the DCI paradigm is to store context-specific behavior not in models, but in specific context classes which we then inject the models into. These context classes will contain all the context-specific behavior, and will extend and manipulate the data-containing models as necessary to get the desired result.

The example that Victor gives is of a bank transfer. In the example, the account model contains no knowledge of how to conduct a bank transfer – it only knows how to store and modify its balance. Victor implement the “funds transfer” interaction by created a TransferringMoney class, which accepts two account objects, as well as a balance, extends both account objects with context-specific methods, and then sends the necessary messages to both accounts to execute the transfer.

The advantage of this style is that the Account class is kept quite lightweight, with context-specific behavior being stored in a class that represents the context. This means that it should be easy to reuse the Account class in new contexts, extending it with context-specific methods as necessary.

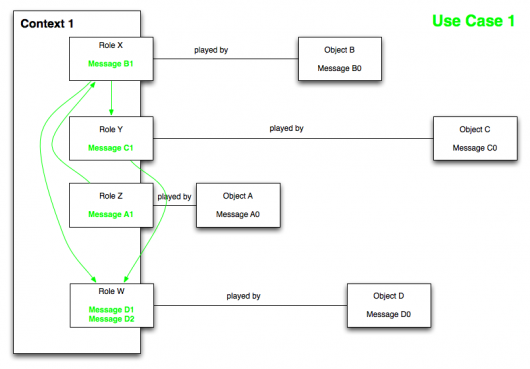

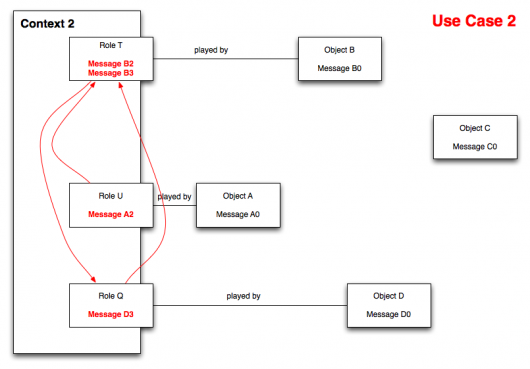

These diagrams (also taken from Victor’s post) illustrate the implementation of DCI, using the same four objects to implement two separate sets of interactions.

Sounds great, but…

DCI is not without its shortcomings. The biggest shortcoming (to my mind) is that models lose reusability. When behavior is limited only to one context, then it becomes more difficult to reuse that behavior in new contexts.

For example, if Context 3 contains methods A, B, C, and D, and we decide later on that we want to create a Context 4 that re-uses methods B and D, we’ll have to either duplicate the code in the new context or extract duplicate code into modules to be shared across contexts. This would result in either a loss of DRYness or an annoying increase in complexity associated with maintaining small pieces of behavior.

For example, returning to the bank account example above, say we want to add a context where a user is withdrawing funds from an ATM. In this case, we would want to reuse the transfer_out behavior from the bank transfer context, but without the transfer_in behavior associated with an account-to-account transfer.

One could imagine achieving this by extracting the transfer_out method into some module (TransferOuttable?) that could be included into both contexts – but at that point, why not simply write transfer_out into the Account class and be done with it?

DCI seems to have been designed to increase clarity around contexts and interactions, at the expense of some reusability. What is there was some way to… have both?

Integration tests to the rescue!

DCI was created to address a perceived shortcoming in Object-Oriented design – namely, that information about interactions at runtime is not discernable based on information about classes and their behavior. This is the very same shortcoming that DHH and Jim Coplien have pointed out in regards to unit testing, in their articles here and here.

In his critique of unit testing (which I grapple with in an earlier post), Jim makes the point that unit testing, while providing feedback on the behavior of class methods in isolation, they provide no feedback on how these classes interact at runtime. He goes on to make the point that runtime interactions are much more complex and dynamic than methods tested in isolation, and consequently unit testing can provide a false sense of security while failing to actually test behavior at a crucial level of abstraction (runtime).

Both James and D end up advocating for integration tests (and other tests at higher levels of abstraction) in lieu of unit tests, arguing that these tests provide more relevant feedback and protection than do unit tests.

What I am going to propose here is that we can use integration tests to capture the benefits of Data, Context, and Interaction design without the downsides of loss of reusability. In other words, to capture and document interaction as an additional layer on top of fully-featured models, rather than in lieu of them.

But… how?

Let’s return to the earlier example of the bank account transfer. Now imagine that, instead of organizing all the transfer-specific behavior into a context “class” and injecting the account objects as dependencies, we built all the transfer behavior into the Account class (as we would do in vanilla Object Oriented design), and captured the interactions in an integration test, something like account_transfer_spec.rb.

Within the individual tests, then, we could instantiate the objects and set them equal to variables representing their roles, before taking them through the series of operations representing the interaction.

It would look something like the following:

require 'spec_helper'

describe "Account Transfer" do

let(:source_account) { Account.new(balance: 100) }

let(:destination_account) { Account.new(balance: 100) }

describe 'transfer interactions' do

it "can transfer $20" do

expect(destination_account).to receive(:transfer_in).with(20)

source_account.transfer_to(destination_account, 20)

expect(destination_account.balance).to eq(120)

expect(source_account.balance).to eq(20)

end

it "raises an error given insufficient funds" do

expect(source_account.transfer_to(destination_account, 200)).to raise_error(RuntimeError, "Insufficient Funds")

end

# Any other interactions you'd like to test and document

end

endYou’ll notice that the tests are more granular than a typical integration test, with multiple assertions being contained within a single test. While this could be considered bad form, this is done with the intention of a single test being meant to document a complete interaction, rather than some smaller unit of behavior. My hope was that, by creating a 1:1 ratio of interaction to test, the test files would be stronger sources of documentation about high-level design.

I’ll submit my thesis that this test file captures much (but not all) of the benefit of DCI-style programming, in that a developer can easily read through this test file and understand how these objects are meant to be interacting with each other (given their roles), while simultaneously preserving the modularity benefits of vanilla class-based Object-Oriented design, by keeping the methods themselves inside of their classes.

In addition, this style of testing brings with it all of the other benefits of integration tests, as DHH, Jim Coplien, and others have been recently discussing.

Where this method fails to preserve an advantage of DCI is context-level flexibility – to change the context interaction, you’ll still have to open up the class and change the methods there (and then go back and change the test file), rather than be able to change the methods right there in the context. It seems as though flexibility at the context level is inversely proportional to flexibility at the class and overall design levels – it’ll be up to you to decide what works best for the challenge you’re facing.

Wrapping up

If you’ve been following the unit vs. integration test debate that’s been simmering in the Ruby community this past month, you have probably come to appreciate the relative pros and cons of various testing styles, and come to understand the importance of testing and documenting your program at various levels of abstraction.

DCI is a programming paradigm designed to rectify some of the shortcomings of unit-level design by encouraging more design at the interaction-level, but at the cost of some modularity. Wikipedia describes DCI as having the following four advantages:

- To improve the readability of object-oriented code by giving system behavior first-class status;

- To cleanly separate code for rapidly changing system behavior (what the system does) from code for slowly changing domain knowledge (what the system is), instead of combining both in one class interface;

- To help software developers reason about system-level state and behavior instead of only object state and behavior;

- To support an object style of thinking that is close to peoples’ mental models, rather than the class style of thinking that overshadowed object thinking early in the history of object-oriented programming languages.

Through the use of integration tests, we should be able to capture much of the benefit of DCI-style programming (aspects of 1, 3, and 4 above) by providing a single source which contains all the information (thus serving as documentation) about a single context, while simultaneously preserving the modularity of class-based OO design. In addition, integration testing goes further than DCI design alone by providing verification of the correctness of the classes and methods, and proving that they work in context.

The question of testing and document behavior and interaction is both compelling and complex, with no single best answer. It will be exciting to see how the thinking about testing and design will evolve over the upcoming months and years – helping to bring about better software and better experiences.