The Problem of Information II

1

In Part I, we established the data processing inequality and used it to conclude that no analysis of data can increase the amount of information we have about the world, beyond the information provided by the data itself:

\[X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow \hat{X}\] \[\Rightarrow\] \[I(\hat{X};X) \leq I(Y;X)\]We’re not quite done. The fundamental problem is not simply learning about the world, but rather human learning about the world. The full model might look something like this:

\[\text{world} \rightarrow \text{measurements} \rightarrow \text{analysis} \rightarrow [perception] \rightarrow \text{understanding}\]Incorporating the human element requires a larger model and additional tools.

2

A channel is the medium by which information travels from one point to another:

\[X \rightarrow [channel] \rightarrow Y\]At one end, we have information, encoded as some sort of representation. We send this representation through the channel. A receiver at the other end receives some signal, which they reconstruct into some sort of representation. Hopefully, this reconstruction is close to the original representation.

No (known) channel is perfect. There is too much uncertainty in their underlying physics and mechanics of their actual construction. Mistakes are made. Bits are flipped. We say the amount of information that a channel can reliably transmit is that channels capacity. For a given channel, capacity is denoted \(C\), and for input variable \(X\) and output varaible \(Y\) it is defined like this (\(\triangleq\) means “defined as”):

\[C_{channel} \triangleq max_{P(X)} I(X; Y)\]This means that the capacity is equal to the maximum mutual information between \(X\) and \(Y\), over all distributions on \(X\). Using a well-known identity, we can rewrite this equation as follows:

\[I(X; Y) = H(Y) - H(Y|X)\]This shows us that capacity is a function of both the entropy of \(Y\) and the conditional entropy of \(Y\) given \(X\). The conditional entropy represents the uncertainty in \(Y\) given \(X\) – in other words, the quality of the channel (for a perfect channel, this value would be \(0\)). \(H(Y)\) is a function of \(H(X)\) and is what we try to maximize when determining capacity.

Observe that capacity \(C\) is a function of both the channel and the randomeness input. For a fixed channel, capacity is a function of the input. For a fixed input, the capacity is a function of the channel (here is it known as “distortion”).

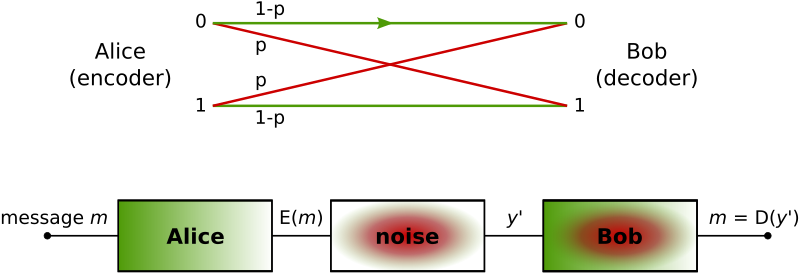

Below is an example of what is known as a “Binary Symmetric Channel” – a channel with two inputs and outputs (hence binary), and a symmetric probability of error \(p\). This diagram should be interpretable given what we’ve discussed above.

The major result in information theory concerning channel capacity goes like this:

\[P_e^{(n)} \rightarrow 0 \Rightarrow C \geq H(X)\]What this says is that for any transmission scheme where the probability of error (\(P_e^{(n)}\)) goes to zero (as block length \(n\) increases), the capacity of the channel is greater than or equal to the entropy of the input. This is true even for perfect channels (with no error) – meaning that \(H(X)\), the uncertainty inherent in the source, is a fundamental limit in communication.

More plainly, we observe that successful transmission of information requires a channel that is less uncertain than the source you’re trying to transmit. This should be intuitively satisfying. If the channel is more chaotic than what you’re trying to communicate, the output will be more a result of that randomness than whatever message you wanted to send. The flip interpretation, which is less intuitive, is that the more random the source, the more tolerant you can be of noisy channels.

Finally, the converse tells us that any attempt to send a high-entropy source through a low-capacity channel is gauranteed to result in high error.

3

With that established, we can now consider the question of human communication:

\[stimulus \rightarrow [perception] \rightarrow impression\]Let’s consider the metaphor and see if it holds. We want to say that the process of communication is exposing those around us to stimulus (ourselves, media, etc), having that stimulus transmitted through the channels of perception, and ultimately represented in the mind as some sort of impression (such as an understanding or feeling). On a first impression, this seems reasonable and general.

What is not present here is the concept of intention. In our communication, we may at various points be trying to teach, persuade, seduce, amuse, mislead, or learn. What is also absent is the concept of “creativity”, or receiving an impression somehow greater than the stimulus. We will return to these questions later and see if we can address it.

Let’s consider a simple case: the teacher trying to teach. We can assume good intention and an emphasis on the transfer of information. We model as follows:

\[teaching \rightarrow [perception] \rightarrow learning\]The “capacity” of human perception is then:

\[C_{perception} = max_{P(teaching)} I(teaching; learning)\] \[I(teaching; learning) = H(learning) - H(learning|teaching)\]This allows us to consider both the randomness of the source (teaching), and the uncertainty in the transmission (perception). We seem justified in proposing the following:

- The challenge of teaching is in maximizing the information the student has about the subject.

- A subject is “harder” if there is more complexity in the subject matter.

- A subject is also “harder” if it is difficult to convey the material in an understandable way.

- A “good” teacher is one who can present the material in a way that is appropriate for the students.

- A “good” student is one who can make the most sense of the material that was presented.

Let’s begin with (4), the idea of material being tailored to the student, or the input being tailored to the channel. Intuitively, we would like to say that a good teacher can change the teaching (the stimulus) they present to the student in order to maximize the student’s learning.

First, consider that material may be too advanced for some students. We would like to say then that the capacity of that student was insufficient for the complexity of the material. To say this, we must first consider the relationship between randomness with complexity.

4

The language of information theory is the language of randomness and uncertainty. In teaching, it is more comfortable to speak in the language of complexity, difficulty, or challenge. Can these be equivalent?

Entropy is a measure of randomness, and entropy is a function of both 1) the number of possible outcomes of a random process, and 2) the likelihood of the various outcomes. A 100-sided fair die is more random than a 10-sided fair die, while a 1000-sided die that always came up 7 is not really random at all.

Complexity, on the other hand, can be understood as the number and nature of the relationships among various parts of a system. We can perhaps formalized this as the number of pathways by which a change in one part of the system can affect the overall state of the system.

To argue equivalence, we assert that there is always some degree of uncertainty in any system, or in any field of study. In math, these are formalized as variables. In history, these can be the motivations of various actors. The more complex a system, the larger the number of outcomes and the relationship between components. In the language of probability, we say there are more possible outcomes, and that due to the complex relationships between parts, that there are significant odds of many different outcomes.

Consider the example of teaching math. Arithmetic is simpler than geometry, in that the expression

\[2 + 2\]contains fewer conceptual “moving pieces” than the expression

\[\sin(45°)\]Understanding arithmetic requires the student to keep track of the concept of “magnitude” and be able to relate magnitudes via relations of joining (addition and subtraction) and scaling (multiplication and division). It requires the abstract concept of negative numbers.

Understanding geometry requires more tools. It requires students to be able to deal with points in space, and understand how to use the Cartesian plane to represent the relationship between points and numbers. It introduces the idea of “angle” as a new kind of relationship, on top of arithmetic’s “bigger” and “smaller”.

Put another way, arithmetic requires only a line, while geometry requires a plane. More concepts means more possible relationships between objects, which means more possible dimensions of uncertainty, which means more complexity.

We conclude at least a rough equivalence between complexity and uncertainty.

V

Returning to the teaching example, we can now speak in terms of complexity of the material instead of randomness of the source. If material is too complex for the student (\(C < H(X)\)), then the material cannot be taught to that student (yet).

Observe that the channel (the student) is not fixed, but is able to handle increasingly complex subjects over time.

… to be continued?