Exploring the ActiveRecord Metaphor

We’re wrapping up week 4 at the Flatiron School. One of the big topics of the week was ActiveRecord, an ORM (Object-Relational Mapper) that makes it easy to set up and interact with databases within your Ruby program.

Having spent a number of days working with SQLite3 databases using the low-level “native language” of SQL (Structured Query Language), I and the other students quickly realized how much of a help ActiveRecord would be in building complex Ruby applications. ActiveRecord lets you build your database functionality directly into your classes, avoiding the complex syntax of SQL – enabling you to abstract away the database layer, and treat your database interactions like any other object method.

All is not rainbows and kittens, however. Only about 90% rainbows and kittens. ActiveRecord achieves its magic by equipping your classes with a DSL (domain-specific language), a special syntax used only for ActiveRecord. Effective utilization of ActiveRecord requires effective utilization of the ActiveRecord DSL – which requires a thorough understanding of the metaphors underlying ActiveRecord.

ActiveRecord works by creating links between tables in a database (which we don’t see) and their corresponding classes (which we do see). For every database table that we want in our application, ActiveRecord requires us to create a corresponding class which links to it. Every entry in a table (every row) corresponds to an instance of the class, and we interact with the data in the table by sending messages to those instances.

Consider an example: Given a table “authors”, we create a corresponding class “Author”. Every row in the “authors” table would correspond to an instance of Author. By querying that instance, we can edit the information represented by that instance, without ever having to deal with the database directly.

Metaphorically, we can think of a database table representing a library, with each row in the table representing a book in that library. Without ActiveRecord, you would have to go into that library and look up information in the books yourself. With ActiveRecord, however (bear with me), the books come to life. To get information out of the library, just go up to the books and ask them questions. They’ll be surprisingly intelligent. Know what else? THE LIBRARY ITSELF IS ALIVE. You can, like, talk to it. Holy shit.

Cool, huh? The code to build all this looks as follows:

In your migration file, ‘01_create_authors.rb’, located in ‘db/migrations/’:

class CreateAuthors < ActiveRecord::Migration

def change

create_table :authors do |table|

table.string :name

end

end

end

Note: ActiveRecord depends heavily on following convention. In this case, the name of the file (‘01_create_authors’) must correspond to the name of the class (‘CreateAuthors’), by substituting every underscore and lowercase letter for the corresponding uppercase letter. This is not optional.

In your class definition file, ‘author.rb’, located in ‘app/models/’:

class Author < ActiveRecord::Base end

This is really all it takes. ActiveRecord is intelligent enough to recognize the connection between the ‘authors’ table and the Author class – this, in fact, is the intelligence that makes ActiveRecord possible, and powerful.

With me so far? Things are about to speed up.

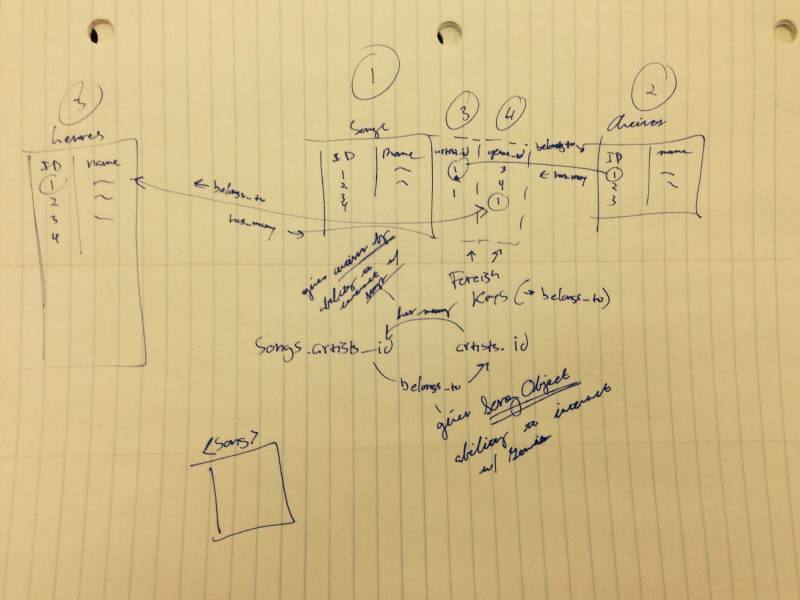

We’ve discussed the way that ActiveRecord abstracts away databases of individual tables, allowing you to interact with objects representing the data in those tables. What about making connections across tables? One of the powers of SQL-based databases is their ability to combine tables and analyze data across multiple tables, using something known as a “join”). Running joins in SQL can be quite complex, and one of the pleasures of ActiveRecord is the simplicity by which it allows you to join information across tables.

Returning to the Author example, let’s add some complexity by introducing a whole new kind of thing: books. Just as with our authors, there is a “books” table, which connects to a Book class. Rows in the “books” table are represented by instances of the Book class, which we interact with as we would any other Ruby object.

What we need, though, is a way for instances of Author to know things about instances of Book, and vice versa. In the real world, authors write books, and every book is written by an author. There’s a relationship there. As developers trying to model the world, we want to be able to represent those relationships. Does ActiveRecord support this?

OF COURSE.

Extending the ActiveRecord metaphor, we can build relationships among different classes by “wiring” them together. We do this with the ‘has_many’ and ‘belongs_to’ methods. We tell the Book class that it ‘belongs_to’ the Author class – or more specifically, that every individual book belongs to an individual author. This way, instances of Book know how to go to the ‘authors’ table and find their author. Likewise, we tell the Author class that every instance of Author ‘has_many’ books – giving instances of Author the ability to go to the “books” table and find their information.

A complete, two-way connection requires you to change both classes. If you tell the Book class that it ‘belongs_to :author’, but forget to tell the Author class that it ‘has_many :books’, then instances of Book will know exactly how to find their author, but instances of Author will have no idea what you’re talking about. Likewise the opposite – if you tell Author that it ‘has_many :books’, but forget to tell Book that it ‘belongs_to :author’, then instances of Author will have no problem finding their books, but instances of Book will just sort of look at you uncomfortably.

How does this work? Through the magic of foreign and primary keys.

What are these things? They are numbers, stored in your database tables, that tell ActiveRecord how to link different classes together.

Primary Key: Every table, when you create it, automatically has a column called ‘id’, which holds a unique number, or id, for every new entry in the database. The first entry has an id of 1, the second entry has an id of 2, and so on. This number is known as the ‘primary key’, and ActiveRecord can use this number to find entries in the database, rather than look things up by their name.

Foreign Key: There’s a little voodoo here. A ‘foreign key’ is another column in a table, separate from the primary key or any other column of information, that contains a number which CORRESPONDS TO ANOTHER TABLE’S PRIMARY KEY. I know, I know. This article should help you make sense of this.

Now, the way ‘belongs_to’ and ‘has_many’ work is that when you tell a Book that it ‘belongs_to :authors’, you’re in fact telling a Book instance to find its foreign key called “author_id” and go and find the row in the ‘authors’ table that has the matching primary key. When you tell an Author that it ‘has_many :books’, you’re telling it to take its primary key and find the row(s) in the books table that has a matching foreign key. That’s ActiveRecord at work. To summarize: ‘has_many’ => take primary key, find matching foreign key. ‘belongs_to’ => take foreign key, find matching primary key.

In other words, ‘has_many :books’ is basically saying: “Hey, Author! Yeah, you with the cappuccino. Listen, there’s a table over yonder called ”books”. There’s gonna be a column in it called “author_id” – yeah, named after you. If the number in that column is the same as your “id”, then that book is yours. People might ask you information about your books, like their name. If anyone asks any of your instances about book stuff, don’t freak out because it’s not in your table – just use your instance’s id number to go track it down from the “books” table. Ok?”

Likewise, ‘belongs_do :author’ loosely translates to: “HEY! HEY! BOOK! Are you listening to me? Look. No, really, just be quiet and listen. There’s going to be a column in you called “author_id”. It might not make much sense to you why it’s there, but just wait. If you look in that closet over there, you’ll find a table called “authors” – right, it’s like the plural version of the main part of the name of the “author_id” column – that’s not an accident. YO! STOP TEXTING. Anyway, if you go to that table, you’ll find a column called “id”. See where I’m going with this? If you take your ”author_id” and head on over to the “authors” table and find the entry in the table where “id” matches your “author_id”, that’s your author. People are gonna ask you about your author eventually, and so when they do, that’s what you do.”

Alright.

Aside: ‘has_many :books’ maps to the “books” table, which makes sense. But ‘belongs_to :author’ maps to the “authors” table, which makes less sense, because ‘:author’ is singular and ‘authors’ is plural. In cases of “belongs_to”, ActiveRecord knows that it should only belong to one, so it expects you to define the connection in the singular – but still knows to go and find the match over in the table with the pluralized name. Technology is amazing, isn’t it?

Let’s take a peek at some more code, starting with the ‘02_create_books.rb’ migration file. (NB: we number the migration files in sequence because we expect them to be executed in sequence. This is a topic beyond this post, but worth reviewing).

class CreateBooks < ActiveRecord::Migration

def change

create_table :books do |table|

table.string :name

table.integer :author_id

end

end

end

So. Notice how in this example, we’ve defined a column called ‘author_id’. That’s where we’ll store the foreign keys. There’s a bit more ActiveRecord intelligence at work here – Active Record knows that ‘author_id’ is a foreign key, meant to correspond to the primary key ‘id’ in the “authors” table. To set up your foreign keys, make sure you include columns in your migration files that follow the following convention: [table name: plural] => [column name: singular]_id. So to link to the ‘authors’ table, you create a column called ‘author_id’. To link to a hypothetical ‘genres’ table (wink wink), you would set up a column called ‘genre_id’. And so on. That’s all you need to do on the database side.

Now let’s look at the classes. Here’s how you set up the ‘belongs_to’ and ‘has_many’ connection:

class Author < ActiveRecord::Base has_many :books end class Book < ActiveRecord::Base belongs_to :author end

Voila. Notice how by defining a simple set of table migrations and building two very spare classes, we’ve created a tremendous amount of functionality. That’s ActiveRecord.

There’s more, though. So far we’ve established two kinds of objects (authors and books), built out the corresponding database infrastructure, and linked them together. But what happens when we want to expand? What happens if we add a third class of object to our world-model?

Let’s try. Let’s add a new kind of thing, genres. First, we’ll toss in a new migration, “03_create_genres.rb”, and fill it with the following:

class CreateGenres < ActiveRecord::Migration

def change

create_table :genres do |table|

table.string :name

end

end

end

Bam. A “genres” table. Good job. Remember what comes next? Of course you do.

class Genre < ActiveRecord::Base has_many :books end

And we make the following edit:

class Book < ActiveRecord::Base belongs_to :author belongs_to :genre end

What’s going on here? First, we create a “genres” table, and then built a “Genre” class to bring the “genres” table TO LIFE. We make sure to let the “Genre” class know that there’s a table called “books” that has a column called “genre_id”, and that it can take the “id” of any of it’s instances and head on down to “books” and look up all the books that it belongs to.

Next, we check in with “Book” and let it know that there’s a whole new table, “genres”, that might come a-knockin. We tell “Book” that its table (the “books” table) has a new column (“genre_id”) and that it can take that number and find it’s matching Genre in the “genres” table by finding the genre with the matching “id”.

Sounds great, right? But WAIT. WE NEVER ADDED THE “genre_id” COLUMN.

Never fear. We can just add another migration, “04_add_genre_to_books.rb”, to add a new column. Voila:

class AddGenreToBooks < ActiveRecord::Migration

def change

add_column :books, :genre_id, :integer

end

end

Whew. Now our models should be wired together beautifully. The “books” table has the foreign keys for both the “authors” and the “genres” table.

We’re almost there. There’s one more bit of sorcery to cover.

We have genres, and authors, and books. Books know about both their genres and their authors, and both authors and genres know about their books. But what if we want to ask an author about her genres? Right now, authors don’t have any way of knowing what their genres are – they don’t have any way of matching their “id” up with information from the “genres” table. Only books know about both.

If only… there was… some way… to connect them. But… that can’t be possible. There’s no way ActiveRecord is that sophisticated. Is there?

class Author < ActiveRecord::Base has_many :books has_many :genres, :through => :books end

No effin way.

YES EFFIN WAY.

What the hell just happened.

Ok, breathe. Remember, Book could find information from both the “authors” and “genres” tables. What we’re doing here is using that functionality to create a bridge between “authors” and “genres”. Basically, Author already knew how to take its “id” and traipse on down to the “books” table to find it’s matching books (by finding the matching “author_id”). What we just did is tell Author that, once it found it’s book, it could go find a column called “genre_id” (which would be right next to “author_id”), take that number, walk a little bit further to the “genres” table, and find the genre that matches the book that matches itself.

Here’s a summary:

Author takes its “id” >> walks on down to “books”, lines up “id” with “author_id”. Scans that same row for “genre_id”, nabs it >> walks on down to “genres”, finds the “id” column that matches the “genre_id” that Author nabbed from the “books” table >> gets its genre >> celebration.

Now, you might be wondering – does this also wire up a connection going the other way? In other words, since Author can now answer questions about Genre, can Genre also answer questions about Author? Let’s walk through it.

Genre takes its “id”, and using ‘has_many :books’, pops on in to the “books” table for a bit of tea. While there, it takes a peek at the “genre_id” column, looking for any values that match up with it’s “id”, eventually finding a few. Then… nothing. Genre has no idea that, literally two inches away, is a whole other column called “author_id”, full of delicious goodness just waiting to be accessed. Genre looks around, confused, feeling vaguely uneasy, the butt of some cosmic joke. Eventually Genre slinks home, dejected, and self-soothes by cracking open a dusty copy of “Watchmen” and thinking about ethics and the frailty of mankind.

How can we help poor Genre? Try this:

class Genre < ActiveRecord::Base has_many :books has_many :authors, :through => :books end

Ladies and gentlemen, ActiveRecord.